Traveling within the World

Linking your favorite traveling artists across the globe

Early Smoothbore Cannon

In view of the range Collado ascribes to the culverin, some remarks on gun performances are in order. "Greatest random" was what the old time gunner called his maximum range, and random it was. Beyond point-blank range, the gunner was never sure of hitting his target. So with smoothbores, long range was never of great importance. Culverins, with their thick walls, long bores, and heavy powder charges, achieved distance; but second class guns like field "cannon," with less metal and smaller charges, ranged about 1,600 yards at a maximum, while the effective range was hardly more than 500. Heavier pieces, such as the French 33-pounder battering cannon, might have a point-blank range of 720 yards; at 200-yard range its ball would penetrate from 12 to 24 feet of earthwork, depending on how "poor and hungry" the earth was. At 130 yards a Dutch 48-pounder cannon put a ball 20 feet into a strong earth rampart, while from 100 yards a 24-pounder siege cannon would bury the ball 12 feet.

But generalizations on early cannon are difficult, for it is not easy to find two "mathematicians" of the old days whose ordnance lists agree. Spanish guns of the late 1500's do, however, appear to be larger in caliber than pieces of similar name in other countries, as is shown by comparing the culverins: the smallest Spanish culebrina was a 20-pounder, but the French great couleurine of 1551 was a 15-pounder and the typical English culverin of that century was an 18-pounder. Furthermore, midway of the 1500's, Henry II greatly simplified French ordnance by holding his artillery down to the 33-pounder cannon, 15-pounder great culverin, 7-1/2-pounder bastard culverin, 2-pounder small culverin, a 1-pounder falcon, and a 1/2-pounder falconet. Therefore, any list like the one following must have its faults:

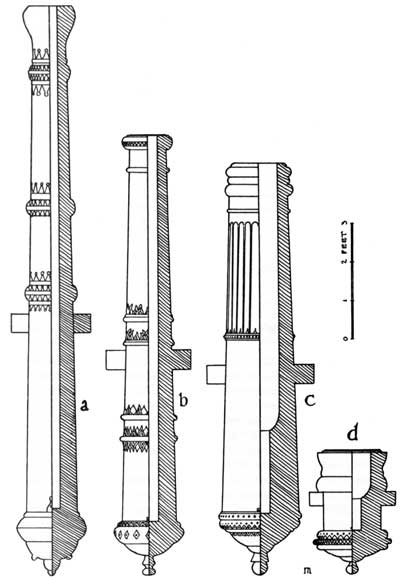

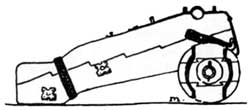

Soon after he found he could hurl a rock with his good right arm, man learned about trajectory—the curved path taken by a missile through the air. A baseball describes a "flat" trajectory every time the pitcher throws a hard, fast one. Youngsters tossing the ball to each other over a tall fence use "curved" or "high" trajectory. In artillery, where trajectory is equally important, there are three main types of cannon: (1) the flat trajectory gun, throwing shot at the target in relatively level flight; (2) the high trajectory mortar, whose shell will clear high obstacles and descend upon the target from above; and (3) the howitzer, an in-between piece of medium-high trajectory, combining the mobility of the fieldpiece with the large caliber of the mortar.The Spaniard, Luis Collado, mathematician, historian, native of Lebrija in Andalusia, and, in 1592, royal engineer of His Catholic Majesty's Army in Lombardy and Piedmont, defined artillery broadly as "a machine of infinite importance." Ordnance he divided into three classes, admittedly following the rules of the "German masters, who were admired above any other nation for their founding and handling of artillery." Culverins and sakers (Fig. 23a) were guns of the first class, designed to strike the enemy from long range. The battering cannon (fig. 23b) were second class pieces; they were to destroy forts and walls and dismount the enemy's machines. Third class guns fired stone balls to break and sink ships and defend batteries from assault; such guns included the pedrero, mortar, and bombard (fig. 23c,d).Collado's explanation of how the various guns were invented is perhaps naive, but nevertheless interesting: "Although the main intent of the inventors of this machine [artillery] was to fire and offend the enemy from both near and afar, since this offense must be in diverse ways it so happened that they formed various classes in this manner: they came to realize that men were not satisfied with the espingardas [small Moorish cannon], and for this reason the musket was made; and likewise the esmeril and the falconet. And although these fired longer shots, they made the demisaker. To remedy a defect of that, the sakers were made, and the demiculverins and culverins. While they were deemed sufficient for making a long shot and striking the enemy from afar, they were of little use as battering guns because they fire a small ball. So they determined to found a second kind of piece, wherewith, firing balls of much greater weight, they might realize their intention. But discovering like-wise that this second kind of piece was too powerful, heavy and costly for batteries and for defense against assaults or ships and galleys, they made a third class of piece, lighter in metal and taking less powder, to fire balls of stone. These are the commonly called cañones de pedreros. All the classes of pieces are different in range, manufacture and design. Even the method of charging them is different."

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Name of gun | Weight of ball (pounds) |

Length of gun (in calibers) |

Range in yards | Popular caliber | |

| Point- blank |

Maximum | ||||

| Esmeril | 1/2 | 208 | 750 | 1/2-pounder esmeril. | |

| Falconete | 1 to 2 | 1-pounder falconet. | |||

| Falcon | 3 to 4 | 417 | 2,500 | 3-pounder falcon. | |

| Pasavolante | 1 to 15 | 40 to 44 | 500 | 4,166 | 6-pounder pasavolante. |

| Media sacre | 5 to 7 | 417 | 3,750 | 6-pounder demisaker. | |

| Sacre | 7 to 10 | 9-pounder saker. | |||

| Moyana | 8 to 10 | shorter than saker | 9-pounder moyenne. | ||

| Media culebrina | 10 to 18 | 833 | 5,000 | 12-pounder demiculverin. | |

| Tercio de culebrina | 14 to 22 | 18-pounder third-culverin. | |||

| Culebrina | 20, 24, 25, 30, 40, 50 | 30 to 32 | 1,742 | 6,666 | 24-pounder culverin. |

| Culebrina real | 24 to 40 | 30 to 32 | 32-pounder culverin royal. | ||

| Doble culebrina | 40 and up | 30 to 32 | 48-pounder double culverin. | ||

(inches)

of gun

(pounds)

of shot

(pounds)

charge

(pounds)

Like many gun names, the word "culverin" has a metaphorical meaning. It derives from the Latin colubra (snake). Similarly, the light gun called áspide or aspic, meaning "asp-like," was named after the venomous asp. But these digressions should not obscure the fact that both culverins and demiculverins were highly esteemed on account of their range and the effectiveness of fire. They were used for precision shooting such as building demolition, and an expert gunner could cut out a section of stone wall with these guns in short order.

As the fierce falcon hawk gave its name to the falcon and falconet, so the saker was named for the saker hawk; rabinet, meaning "rooster," was therefore a suitable name for the falcon's small-bore cousin. The 9-pounder saker served well in any military enterprise, and the moyana (or the French moyenne, "middle-sized"), being a shorter gun of saker caliber, was a good naval piece. The most powerful of the smaller pieces, however, was the pasavolante, distinguishable by its great length. It was between 40 and 44 calibers long! In addition, it had thicker-bore walls than any other small caliber gun, and the combination of length and weight permitted an unusually heavy charge—as much powder as the ball weighed. A 6-pound lead ball was what the typical pasavolante fired; another gun of the same caliber firing an iron ball would be a 4-pounder. The point-blank range of this Spanish gum was a football field's length farther than either the falcon or demisaker.

In today's Spanish, pasavolante means "fast action," a phrase suggestive of the vicious impetuosity to be expected from such a small but powerful cannon. Sometimes it was termed a drajon, the English equivalent of which may be the drake, meaning "dragon"; but perhaps its most popular name in the early days was cerbatana, from Cerebus, the fierce three-headed dog of mythology. Strange things happen to words: a cerbatana in modern Spanish is a pea shooter.

| Spanish name | Weight of ball (pounds) |

Translation |

| Quarto canon | 9 to 12 | Quarter-cannon. |

| Tercio canon | 16 | Third-cannon. |

| Medio canon | 24 | Demicannon. |

| Canon de abatir | 32 | Siege cannon. |

| Doble canon | 48 | Double cannon. |

| Canon de bateria | 60 | Battering cannon. |

| Serpentino | Serpentine. | |

| Quebrantamuro or lonbarda | 70 to 90 | Wallbreaker or lombard. |

| Basilisco | 80 and up | Basilisk. |

The second class of guns were the only ones properly called "cannon's in this early period. They were siege and battering pieces, and in some few respects were similar to the howitzers of later years. A typical Spanish cannon was only about two-thirds as long as a culverin, and the bore walls were thinner. Naturally, the powder charge was also reduced (half the ball's weight for a common cannon, while a culverin took double that amount).

The Germans made their light cannon 18 calibers long. Most Spanish siege and battering guns had this same proportion, for a shorter gun would not burn all the powder efficiently, "which," said Collado, "is a most grievous fault." However, small cannon of 18-caliber length were too short; the muzzle blast tended to destroy the embrasure of the parapet. For this reason, Spanish demicannon were as long as 24 calibers and the quarter-cannon ran up to 28. The 12-pounder quarter-cannon, incidentally, was "culverined" or reinforced so that it actually served in the field as a demiculverin.

The great weight of its projectile gave the double cannon its name. The warden of the Castillo at Milan had some 130-pounders made, but such huge pieces were of little use, except in permanent fortifications. It took a huge crew to move them, their carriages broke under the concentrated weight, and they consumed mountains of munitions. The lombard, which apparently originated in Lombardy, and the basilisk had the same disadvantages. The fabled basilisk was a serpent whose very look was fatal. Its namesake in bronze was tremendously heavy, with walls up to 4 calibers thick and a bore up to 30 calibers long. It was seldom used by the Europeans, but the Turkish General Mustafa had a pair of basilisks at the siege of Malta, in 1565, that fired 150- and 200-pound balls. The 200-pounder gun broke loose as it was being transferred to a homeward bound galley and sank permanently to the bottom of the sea. Its mate was left on the island, where it became an object of great curiosity.

The third class of ordnance included the guns firing stone projectiles, such as the pedrero (or perrier, petrary, cannon petro, etc.), the mortars, and the old bombards like Edinburgh Castle's famous Mons Meg. Bars of wrought iron were welded together to form Meg's tube, and iron rings were clamped around the outside of the piece. In spite of many accidents, this coopering technique persisted through the fifteenth century. Mons Meg was made in two sections that screwed together, forming a piece 13 feet long and 5 tons in weight.

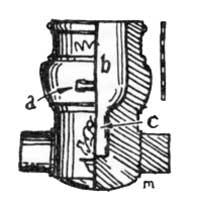

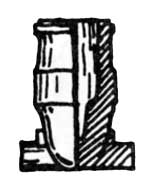

Pedreros (fig. 23c) were comparatively light. The foundryman used only half the metal he would put into a culverin, for the stone projectile weighed only a third as much as an iron ball of the same size, and the bore walls could therefore be comparatively thin. They were made in calibers up to 50-pounders. There was a chamber for the powder charge and little danger of the gun's bursting, unless a foolhardy fellow loaded it with an iron ball. The wall thicknesses of this gun are shown in Figure 24, where the inner circle represents the diameter of the chamber, the next arc the bore caliber, and the outer lines the respective diameters at chase, trunnions, and vent.

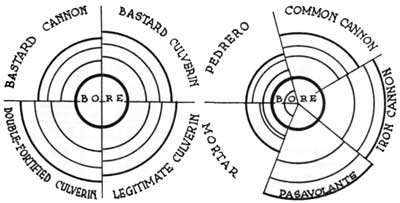

FIGURE 24—HOW MUCH METAL WAS IN EARLY GUNS? The charts compare the wall diameters of sixteenth-seventeenth century types. The center circle represents the bore, while the three outer arcs show the relative thickness of the bore wall at (1) the smallest diameter of the chase, (2) at the trunnions, and (3) at the vent. The small arc inside the bore indicates the powder chamber found in the pedrero and mortar.

Mortars (fig. 23d) were excellent for "putting great fear and terror in the souls of the besieged." Every night the mortars would play upon the town: "it keeps them in constant turmoil, due to the thought that some ball will fall upon their house." Mortars were designed like pedreros, except much shorter. The convenient way to charge them was with saquillos (small bags) of powder. "They require," said Collado, "a larger mouthful than any other pieces."

Just as children range from slight to stocky in the same family, there are light, medium, or heavy guns—all bearing the same family name. The difference lies in how the piece was "fortified"; that is, how thick the founder cast the bore walls. The English language has inelegantly descriptive terms for the three degrees of "fortification": (1) bastard, (2) legitimate, and (3) double-fortified. The thicker-walled guns used more powder. Spanish double-fortified culverins were charged with the full weight of the ball in powder; four-fifths that amount went into the legitimate, and only two-thirds for the bastard culverin. In a short culverin (say, 24 calibers long instead of 30), the gunner used 24/30 of a standard charge.

The yardstick for fortifying a gun was its caliber. In a legitimate culverin of 6-inch caliber, for instance, the bore wall at the vent might be one caliber (16/16 of the bore diameter) or 6 inches thick; at the trunnions it would be 10/16 or 4-1/8 inches, and at the smallest diameter of the chase, 7/16 or 2-5/8 inches. This table compares the three degrees of fortification used in Spanish culverins:

| Wall thickness in 8ths of caliber | |||

| Vent | Trunnion | Chase | |

| Bastard culverin | 7 | 5 | 3 |

| Legitimate culverin | 8 | 5-1/2 | 3-1/2 |

| Double-fortified culverin | 6-1/2 | 9 | 4 |

As with culverins, so with cannon. This is Collado's table showing the fortification for Spanish cannon:

| Wall thickness in 8ths of caliber | |||

| Vent | Trunnion | Chase | |

| Cañon sencillo (light cannon) | 6 | 4-1/2 | 2-1/2 |

| Cañon común (common cannon) | 5 | 7 | 3-1/2 |

| Canon reforzado (reinforced cannon) | 5-1/2 | 8 | 3-1/2 |

Since cast iron was weaker than bronze, the walls of cast-iron pieces were even thicker than the culverins. Spanish iron guns were founded with 300 pounds of metal for each pound of the ball, and in lengths from 18 to 20 calibers. English, Irish, and Swedish iron guns of the period, Collado noted, had slightly more metal in them than even the Spaniards recommended.

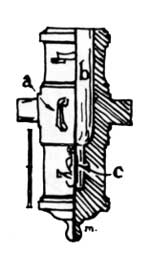

FIGURE 25—SIXTEENTH CENTURY CHAMBERED CANNON. a—"Bell-chambered" demicannon. b—Chambered demicannon.

Another way the designers tried to gain strength without loading the gun with metal was by using a powder chamber. A chambered cannon (fig. 25b) might be fortified like either the light or the common cannon, but it would have a cylindrical chamber about two-thirds of a caliber in diameter and four calibers long. It was not always easy, however, to get the powder into the chamber. Collado reported that many a good artillerist dumped the powder almost in the middle of the gun. When his ladle hit the mouth of the chamber, he thought he was at the bottom of the bore! The cylindrical chamber was somewhat improved by a cone-shaped taper, which the Spaniards called encampanado or "bell-chambered." A cañon encampanado (fig. 25a) was a good long-range gun, strong, yet light. But it was hard to cut a ladle for the long, tapered chamber.

Of all these guns, the reinforced cannon, was one of the best. Since it had almost as much metal as a culverin, it lacked the defects of the chambered pieces. A 60-pounder reinforced cannon fired a convenient 55-pound ball, was easy to move, load, and clean, and held up well under any kind of service. It cooled quickly. Either cannon powder or fine powder (up to two-thirds the ball's weight) could be used in it. Reinforced cannon were an important factor in any enterprise, as King Philip's famed "Twelve Apostles" proved during the Flanders wars.

| Spanish guns | Thickness of bore wall in 8ths of the caliber |

English guns | ||

| Vent | Trunnions | Chase | ||

| Light cannon; bell-chambered cannon | 6 | 4-1/2 | 2-1/2 | Bastard cannon. |

| Demicannon | 6 | 5 | 3 | |

| Common cannon; common siege cannon | 7 | 5 | 3-1/2 | |

| Light culverin; common battering cannon | 7 | 5 | 3 | Bastard culverin; legitimate cannon. |

| Common culverin; reinforced cannon | 8 | 5-1/2 | 3-1/2 | Legitimate culverin; double-fortified cannon. |

| Legitimate culverin | 9 | 6-1/2 | 4 | Double-fortified culverin. |

| Cast-iron cannon | 10 | 8 | 5 | |

| Pasavolante | 11-1/2 | 8-1/2 | 5-1/2 | |

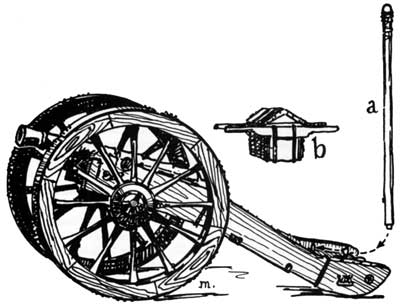

While there was little real progress in mobility until the days of Gustavus Adolphus, the wheeled artillery carriage seems to have been invented by the Venetians in the fifteenth century. The essential parts of the design were early established: two large, heavy cheeks or side pieces set on an axle and connected by transoms. The gun was cradled between the cheeks, the rear ends of which formed a "trail" for stabilizing and maneuvering the piece.

Wheels were perhaps the greatest problem. As early as the 1500's carpenters and wheelwrights were debating whether dished wheels were best. "They say," reported Collado, "that the [dished] wheel will never twist when the artillery is on the march. Others say that a wheel with spokes angled beyond the cask cannot carry the weight of the piece without twisting the spoke, so the wheel does not last long. I am of the same opinion, for it is certain that a perpendicular wheel will suffer more weight than the other. The defect of twisting under the pieces when on the march will be remedied by making the cart a little wider than usual." However, advocates of the dished wheel finally won.

Tags:

Replies to This Discussion

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on February 18, 2011 at 3:51pm

-

Smoothbore Cannons

of the Later PeriodFor both bronze and iron guns, the above figures were the same, but for bronze, Armstrong divided the caliber into 16 parts; for iron it was only 14 parts. The walls of an iron gun thus were slightly thicker than those of a bronze one.

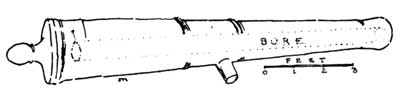

This eighteenth century cannon was a cast gun, but hoops and rings gave it the built-up look of the barrel-stave bombard, when hoops were really functional parts of the cannon. Reinforces made the gun look like "three frustums of cones joined together, so as the lesser base of the former is always greater than the greatest of the succeeding one." Ornamental fillets, astragals, and moldings, borrowed from architecture, increased the illusion of a sectional piece. Tests with 24-pounders of different lengths showed guns from 18 to 21 calibers long gave generally the best performance, but what was true for the 24-pounder was not necessarily true for other pieces. Why was the 32-pounder "brass battering piece" 6 inches longer than its 42-pounder brother? John Müller wondered about such inconsistencies and set out to devise a new system of ordnance for Great Britain,

Like many men before him, Müller sought to increase the caliber of cannon without increasing weight. He managed it in two ways: he modified exterior design to save on metal, and he lessened the powder charge to permit shortening and lightening the gun. Müller's guns had no heavy reinforces; the metal was distributed along the bore in a taper from powder chamber to muzzle swell. But realizing man's reluctance to accept new things, he carefully specified the location and size for each molding on his gun, protesting all the while the futility of such ornaments. Not until the last half of the next century were the experts well enough versed in metallurgy and interior ballistics to slough off all the useless metal.

So, using powder charges about one-third the weight of the projectile, Muller designed 14-caliber light field pieces and 15-caliber ship guns. His garrison and battering cannon, where weight was no great disadvantage, were 18 calibers long. The figures in the table following represent the principal dimensions for the four types of cannon—all cast-iron except for the bronze siege guns. The first line in the table shows the length of the cannon. To proportion the rest of the piece, Müller divided the shot diameter into 24 parts and used it as a yardstick. The caliber of the gun, for instance, was 25 parts, or 25/24th of the shot diameter. The few other dimensions—thickness of the breech, length of the gun before the barrel began its taper, fortification at vent and chase—were expressed the same way.

From the guns of Queen Elizabeth's time came the 6-, 9-, 12-, 18-, 24-, 32-, and 42-pounder classifications adopted by Cromwell's government and used by the English well through the eighteenth century. On the Continent, during much of this period, the French were acknowledged leaders. Louis XIV (1643-1715) brought several foreign guns into his ordnance, standardizing a set of calibers (4-, 8-, 12-, 16-, 24-, 32-, and 48-pounders) quite different from Henry II's in the previous century.

The cannon of the late 1600's was an ornate masterpiece of the foundryman's art, covered with escutcheons, floral relief, scrolls, and heavy moldings, the most characteristic of which was perhaps the banded muzzle (figs. 23b-c, 25, 26a-b), that bulbous bit of ornamentation which had been popular with designers since the days of the bombards. The flared or bell-shaped muzzle (figs. 23a, 26c, 27) did not supplant the banded muzzle until the eighteenth century, and, while the flaring bell is a usual characteristic of ordnance founded between 1730 and 1830, some banded-muzzle guns were made as late as 1746 (fig. 26a).

By 1750, however, design and construction were fairly well standardized in a gun of much cleaner line than the cannon of 1650. Although as yet there had been no sharp break with the older traditions, the shape and weight of the cannon in relation to the stresses of firing were becoming increasingly important to the men who did the designing.

FIGURE 26—EIGHTEENTH CENTURY CANNON. a—Spanish bronze 24-pounder of 1746. b—French bronze 24-pounder of the early 1700's. c—British iron 6-pounder of the middle 1700's. The 6-pounder is part of the armament at Castillo de San Marcos.Conditions in eighteenth century Great Britain were more or less typical: in the 1730's Surveyor-General Armstrong's formulae for gun design were hardly more than continuations of the earlier ways. His guns were about 20 calibers long, with these outside proportions:

1st reinforce = 2/7 of the gun's length.

2d reinforce = 1/7 plus 1 caliber.

chase = 4/7 less 1 caliber.

The trunnions, about a caliber in size, were located well forward (3/7 of the gun's length) "to prevent the piece from kicking up behind" when it was fired. Gunners blamed this bucking tendency on the practice of centering the trunnions on the lower line of the bore. "But what will not people do to support an old custom let it be ever so absurd?" asked John Müller, the master gunner of Woolwich. In 1756, Müller raised the trunnions to the center of the bore, an improvement that greatly lessened the strain on the gun carriage.

FIGURE 27—SPANISH 24-POUNDER CAST-IRON GUN (1693). Note the modern lines of this cannon, with its flat breech and slight muzzle swell.The caliber of the gun continued to be the yardstick for "fortification" of the bore walls:

Vent 16 parts End of 1st reinforce 14-1/2 do Beginning of second reinforce 13-1/2 do End of second reinforce 12-1/2 do Beginning of chase 11-1/2 do End of chase 8 do

Field Ship Siege Garrison Length in calibers 14 15 18 18 (Other proportions in 24ths of the shot diameter) Caliber 25 25 25 25 Thickness of breech 14 24 16 24 Length from breech to taper 39 49 40 49 Thickness at vent 16 25 18 25 Thickness at muzzle 8 12-1/2 9 12-1/2 The heaviest of Müller's garrison guns averaged some 172 pounds of iron for every pound of the shot, while a ship gun weighed only 146, less than half the iron that went into the sixteenth century cannon. And for a seafaring nation such as Britain, these were important things. Perhaps the opposite table will give a fair idea of the changes in English ordnance during the eighteenth century. It is based upon John Müller's lists of 1756; the "old" ordnance includes cannon still in use during Müller's time, while the "new" ordnance is Müller's own.

Calibers and lengths of principal eighteenth century English cannon Caliber Field Ship Siege Garrison Iron Bronze Iron Bronze Iron Bronze Iron Bronze Iron Bronze 1-1/2 pounder

6'0"

3-pounder 3'6" 3'3"

3'6" 4'6" 3'6" 7'0"

4'6" 4'2" 4-pounder

6'0"

6-pounder 4'6" 4'1" 8'0" 4'4" 7'0" 4'4" 8'0"

6'6" 5'3" 9-pounder

4'8"

5'0" 7'0" 5'0" 9'0"

7'0" 6'0" 12-pounder 5'0" 5'1" 9'0" 5'6" 9'0" 5'6" 9'0" 6'7" 8'0" 6'7" 18-pounder

5'10"

6'4" 9'0" 6'4" 9'6" 7'6" 9'0" 7'6" 24-pounder 5'6" 6'5" 9'6" 7'0" 9'0" 7'0" 9'6" 8'4" 9'0" 8'4" 32-pounder

7'6" 9'6" 7'6" 10'0" 9'2" 9'6" 9'2" 36-pounder

7'10"

9'6"

42-pounder

9'6" 8'4" 10'0" 8'4" 9'6" 10'0"

10'0" 48-pounder

8'6"

8'6"

10'6"

Windage in the English gun of 1750 was about 20 percent greater than in French pieces. The English ratio of shot to caliber was 20:21; across the channel it was 26:27. Thus, an English 9-pounder fired a 4.00-inch ball from a 4.20-inch bore; the French 9-pounder ball was 4.18 inches and the bore 4.34.

The British figured greater windage was both convenient and economical: windage, said they, ought to be just as thick as the metal in the gunner's ladle; standing shot stuck in the bore and unless it could be loosened with the ladle, had to be fired away and lost. John Müller brushed aside such arguments impatiently. With a proper wad over the shot, no dust or dirt could get in; and when the muzzle was lowered, said Müller, the shot "will roll out of course." Besides, compared with increased accuracy, the loss of a shot was trifling. Furthermore, with less room for the shot to bounce around the bore, the cannon would "not be spoiled so soon." Müller set the ratio of shot to caliber as 24:25.

In the 1700's cast-iron guns became the principal artillery afloat and ashore, yet cast bronze was superior in withstanding the stresses of firing. Because of its toughness, less metal was needed in a bronze gun than in a cast-iron one, so in spite of the fact that bronze is about 20 percent heavier than iron, the bronze piece was usually the lighter of the two. For "position" guns in permanent fortifications where weight was no disadvantage, iron reigned supreme until the advent of steel guns. But non-rusting bronze was always preferable aboard ship or in seacoast forts.

Müller strongly advocated bronze for ship guns. "Notwithstanding all the precautions that can be taken to make iron guns of a sufficient strength," he said, "yet accidents will sometimes happen, either by the mismanagement of the sailors, or by frosty weather, which renders iron very brittle." A bronze 24-pounder cost £156, compared with £75 for the iron piece, but the initial saving was offset when the gun wore out. The iron gun was then good for nothing except scrap at a farthing per pound, while the bronze cannon could be recast "as often as you please."

In 1740, Maritz of Switzerland made an outstanding contribution to the technique of ordnance manufacture. Instead of hollow casting (that is, forming the bore by casting the gun around a core), Maritz cast the gun solid, then drilled the bore, thus improving its uniformity. But although the bore might be drilled quite smooth, the outside of a cast-iron gun was always rough. Bronze cannon, however, could be put in the lathes to true up even the exterior. While after 1750 the foundries seldom turned out bronze pieces as ornate as the Renaissance culverins, a few decorations remained and many guns were still personalized with names in raised letters on the gun. Castillo de San Marcos has a 4-pounder "San Marcos," and, indeed, saints' names were not uncommon on Spanish ordnance. Other typical names were El Espanto (The Terror), El Destrozo (The Destroyer), Generoso (Generous), El Toro (The Bull), and El Belicoso (The Quarrelsome One).

In some instances, decoration was useful. The French, for instance, at one time used different shapes of cascabels to denote certain calibers; and even a fancy cascabel shaped like a lion's head was always a handy place for anchoring breeching tackle or maneuvering lines. The dolphins or handles atop bronze guns were never merely ornaments. Usually they were at the balance point of the gun; tackle run through them and hooked to the big tripod or "gin" lifted the cannon from its carriage.

-

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on February 18, 2011 at 3:51pm

-

Garrison & Ship Cannons

The total number of Castillo guns in service at this date was 27, but there were close to a dozen unmounted pieces on hand, including a pair of pedreros. The armament was gradually increased to 70-odd guns as construction work on the fort made additional space available, and as other factors warranted more ordnance. Below is a summary of Castillo armament through the years:

Armament of Castillo de San Marcos, 1683-1763

Cannon for permanent fortifications were of various sizes and calibers, depending upon the terrain that had to be defended. At Castillo de San Marcos, for instance, the strongest armament was on the water front; lighter guns were on the land sector, an area naturally protected by the difficult terrain existing in the colonial period.

FIGURE 28—EIGHTEENTH CENTURY SPANISH GARRISON GUNBefore the Castillo was completed, guns were mounted only in the bastions or projecting corners of the fort. A 1683 inventory clearly shows that heaviest guns were in the San Agustín, or southeastern bastion, commanding not only the harbor and its entrance but the town of St. Augustine as well San Pablo, the northwestern bastion, overlooked the land approach to the Castillo and the town gate; and, though its armament was lighter, it was almost as numerous as that in San Agustín. Bastion San Pedro to the southwest was within the town limits, and its few light guns were a reserve for San Pablo. The watchtower bastion of San Carlos over looked the northern marshland and the harbor; its armament was likewise small. The following list details the variety and location of the ordnance:

Cannon mounted at Castillo de San Marcos in 1683

Location

No.

Caliber

Class

Metal

Remarks

In the bastion of San Agustín

1

1

2

1

1

1

1

1

140-pounder

18-pounder

16-pounder

12-pounder

12-pounder

8-pounder

7-pounder

4-pounder

3-pounderCannon

. . do . .

. . do . .

. . do . .

. . do . .

. . do . .

. . do . .

. . do . .

. . do . .Bronze

. . do . .

Iron

Bronze

Iron

Bronze

Iron

. . do . .

BronzeCarriage battered.

New carriage.

Old carriages, wheels bad.

New carriage.

do.

Old carriage.

Carriage bad.

New carriage.

do.In the bastion of San Pablo

1

1

2

1

1

116-pounder

10-pounder

9-pounder

7-pounder

7-pounder

5-pounderDemicannon.

Demiculverin.

Cannon

Demiculverin

Cannon

doIron

Bronze

Iron

Bronze

Iron doOld carriage.

do.

do.

do.

Carriage bad.

New carriage.In the bastion of San Pedro

1

2

2

19-pounder

7-pounder

5-pounder

4-pounderCannon

do.

do.

doIron do

do

BronzeOld carriage.

Carriage bad.

do.

Old carriage.In the bastion of San Carlos

1

1

1

110-pounder

5-pounder

5-pounder

2-pounderCannon

do.

do.

do.Iron

do

Bronze

IronOld carriage.

New carriage.

Good carriage.

New carriage.Kind of gun

1683

1706

1740

1763

Iron

Bronze

Iron

Bronze

Iron

Bronze

Iron

Bronze

2-pounder

1

..

..

+

..

..

..

..

3-pounder

..

1

..

+

2

3

..

..

4-pounder

1

1

*

+

5

1

..

..

5-pounder

4

1

*

+

15

1

..

..

6-pounder

..

..

*

+

5

..

..

..

7-pounder

4

1

*

+

5

2

..

..

8-pounder

..

1

*

+

11

1

5

11

3-1/2-in. carronade

..

..

*

+

..

..

..

..

9-pounder

3

..

*

+

..

..

..

..

10-pounder

1

1

*

+

..

..

6

..

12-pounder

1

1

..

+

..

..

13

..

15-pounder

..

..

..

+

6

..

..

..

16-pounder

3

..

..

+

..

..

2

1

18-pounder

..

1

..

..

4

1

7

..

24-pounder

..

..

..

..

2

..

7

..

33-pounder

..

..

..

..

..

1

..

..

36-pounder

..

..

..

1

..

..

..

1

40-pounder

..

1

..

..

..

..

..

..

24-pounder field howitzer

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

6-in. howitzer

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

8-in. howitzer

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

Small mortar

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

18

6-in. mortar

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

9-in. mortar

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

10-in. mortar

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

Large mortar

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

6

Stone mortar

2

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

Total

20

9

26

9

55

10

40

37

Grand total

29

35

65

77

Armament of Castillo de San Marcos, 1765-1834

Kind of gun

1765

1812

1834

Iron

Bronze

Iron

Bronze

Iron

Bronze

2-pounder

..

..

..

..

..

..

3-pounder

..

..

..

..

..

..

4-pounder

..

..

1

..

..

..

5-pounder

..

..

..

..

..

..

6-pounder

..

1

..

..

3

..

7-pounder

..

..

..

..

..

..

8-pounder

..

..

1

..

..

..

3-1/2-in. carronade

..

..

4

..

..

..

9-pounder

..

..

..

..

..

..

10-pounder

..

..

..

..

..

..

12-pounder

7

..

2

..

..

..

15-pounder

..

..

..

..

..

..

16-pounder

..

..

8

..

..

..

18-pounder

..

..

..

..

4

..

24-pounder

32

..

10

..

5

..

33-pounder

..

..

..

..

..

..

36-pounder

..

..

..

..

..

..

40-pounder

..

..

..

..

..

..

24-pounder field howitzer

..

..

..

..

2

2

6-in. howitzer

..

..

..

2

..

2

8-in. howitzer

..

2

..

..

..

..

Small mortar

..

20

..

..

..

..

6-in. mortar

..

..

..

1

..

1

9-in. mortar

..

..

..

1

..

..

10-in. mortar

..

..

..

..

..

1

Large mortar

..

1

..

..

..

..

Stone mortar

..

..

..

3

..

..

Total

39

24

26

8

14

6

Grand total

63

34

20

*26 guns from 4- to 10- pounders.

+8 guns from 2- to 16-pounders.This tabulation reflects contemporary conditions quite clearly. The most serious invasions of Spanish Florida took place during the first half of the eighteenth century, precisely the time when the Castillo armament was strongest. While most of the guns were in battery condition, the table does have some pieces rated only fair and may also include a few unserviceables. Colonial isolation meant that ordnance often served longer than the normal 1,200-round life of an iron piece. A usual failure was the development of cracks around the vent or in the bore. Sometimes a muzzle blew off. The worst casualties of the 1702 siege came from the bursting of an iron 16-pounder which killed four and seriously wounded six men. At that periods incidentally, culverins were the only guns with the range to reach the harbor bar some 3,000 yards away.

Although when the Spanish left Florida to Britain in 1763 they took serviceable cannon with them, two guns at Castillo de San Marcos National Monument today appear to be seventeenth century Spanish pieces. Most of the 24- and 32-pounder garrison cannon, however, are British-founded, after the Armstrong specifications of the 1730's, and were part of the British armament during the 1760's. Amidst the general confusion and shipping troubles that attended the British evacuation in 1784, some ordnance seems to have been left behind, to remain part of the defenses until the cession to the United States in 1821.

The Castillo also has some interesting United States guns, including a pair of early 24-pounder iron field howitzers (c. 1777-1812). During the 1840's the United States modernized the defenses of Castillo (then known as Fort Marion) by constructing a water battery in the moat behind the seawall. Many of the guns for that battery are extant, including 8-inch Columbiads, 32-pounder cannon, and 8-inch seacoast and garrison howitzers. St. Augustine's Plaza even boasts a converted 32-pounder rifle.

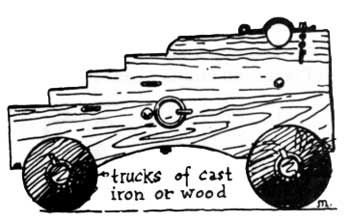

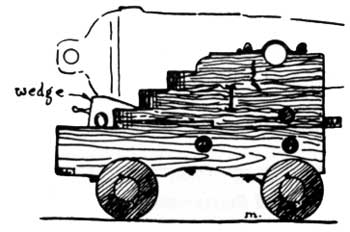

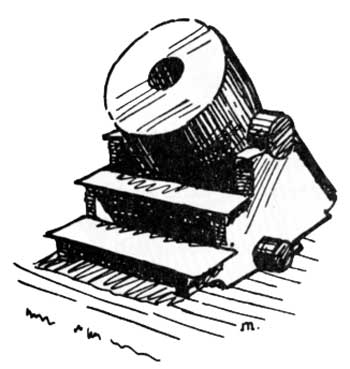

FIGURE 29—VAUBAN'S MARINE CARRIAGE (c.1700).Garrison and ship carriages were far different from field, siege, and howitzer mounts, while mortar beds were in a separate class entirely. Basic proportions for the carriage were obtained by measuring (1) the distance from trunnion to base ring of the gun, (2) the diameter of the base ring, and (3) the diameter of the second reinforce ring. The result was a quadrilateral figure that served as a key in laying out the carriage to fit the gun. Cheeks, or side pieces, of the carriage were a caliber in thickness, so the bigger the gun, the more massive the mount.

A 24-pounder cheek would be made of timber about 6 inches thick. The Spaniards often used mahogany. At Jamestown, in the early 1600's, Capt. John Smith reported the mounting of seven "great pieces of ordnance upon new carriages of cedar," and the French colonials also used this material. British specifications in the mid-eighteenth century called for cheeks and transoms of dry elm, which was very pliable and not likely to split; but some carriages were made of young oak, and oak was standard for United States garrison carriages until it was replaced by wrought iron during the Civil War.

For a four-wheeled British carriage of 1750, height of the cheek was 4-3/4 diameters of the shot, unless some change in height had to be made to fit a gun port or embrasure. To prevent cannon from pushing shutters open when the ship rolled in a storm, lower tier carriages let the muzzle of the gun, when fully elevated, butt against the sill over the gun port.

On the eighteenth century Spanish garrison carriage (fig. 28), no bolts were threaded; all were held either by a key run through a slot in the foot of the bolt, or by bradding the foot over a decorative washer. Compared with American mounts of the same type (figs. 30 and 31), the Spanish carriage was considerably more complicated, due partly to the greater amount of decorative ironwork and partly to the design of the wooden parts which, with their carefully worked mortises, required a craftsman's skill. The cheek of the Spanish carriage was a single great plank. English and American construction called for a built-up cheek of several planks, cleverly jogged or mortised together to prevent starting under the strain of firing.

FIGURE 30—ENGLISH GARRISON CARRIAGE (1756). By substituting wooden wheels for the cast-iron ones, this carriage became a standard naval gun carriage.Müller furnished specifications for building truck (four-wheeled) carriages for 3- to 42-pounders. Aboard ship, of course, the truck carriage was standard for almost everything except the little swivel guns and the mortars.

Carriage trucks (wheels), unless they were made of cast iron, had iron thimbles or bushings driven into the hole of the hub, and to save the wood of the axletree, the spindle on which the wheel revolved was partly protected by metal. The British put copper on the bottom of the spindle; Spanish and French designers put copper on the top, then set iron "axletree bars" into the bottom. These bars strengthened the axletree and resisted wear at the spindle.

A 24-pounder fore truck was 18 inches in diameter. Rear trucks were 16 inches. The difference in size compensated for the slope in the gun platform or deck—a slope which helped to check recoil. Aboard ship, where recoil space was limited, the "kick" of the gun was checked by a heavy rope called a breeching, shackled to the side of the vessel (see fig. 11). Ship carriages of the two- or four-wheel type (fig. 31), were used through the Civil War, and there was no great change until the advent of automatic recoil mechanisms made a stationary mount possible.

FIGURE 31—U. S. NAVAL TRUCK CARRIAGE (1866).With garrison carriages, however, changes came much earlier. In 1743, Fort William on the Georgia coast had a pair of 18-pounders mounted upon "curious moving Platforms" which were probably similar to the traversing platforms standardized by Gribeauval in the latter part of the century. United States forts of the early 1800's used casemate and barbette carriages (fig. 10) of the Gribeauval type, and the traversing platform of these mounts made training (aiming the gun right or left) comparatively easy.

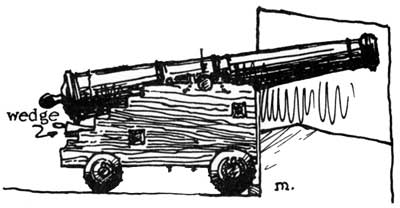

Training the old truck carriage had been heavy work for the handspikemen, who also helped to elevate or depress the gun. Maximum elevation or depression was about 15° each way—about the same as naval guns used during the Civil War. If one quoin was not enough to secure proper depression, a block or a second quoin was placed below the first. But before the gunner depressed a smoothbore below zero elevation, he had to put either a wad or a grommet over the ball to keep it from rolling out.

Ship and garrison cannon were not moved around on their carriages. If the gun had to be taken any distance, it was dismounted and chained under a sling wagon or on a "block carriage," the big wheels of which easily rolled over difficult terrain. It was not hard to dismount a gun: the keys locking the cap squares were removed, and then the gin was rigged and the gun hoisted clear of the carriage.

A typical garrison or ship cannon could fire any kind of projectile, but solid shot, hot shot, bombs, grape, and canister were in widest use. These guns were flat trajectory weapons, with a point-blank range of about 300 yards. They were effective—that is, fairly accurate—up to about half a mile, although the maximum range of guns like the Columbiad of the nineteenth century, when elevation was not restricted by gun port confines, approached the 4-mile range claimed by the Spanish for the sixteenth century culverin. The following ranges of United States ordnance in the 1800's are not far different from comparable guns of earlier date.

Ranges of United States smoothbore garrison guns of 1861 Caliber Elevation Range in yards 18-pounder siege and garrison 5° 0" 1,592 24-pounder siege and garrison 5° 0" 1,901 32-pounder seacoast 5° 0" 1,922 42-pounder seacoast 5° 0" 1,955 8-inch Columbiad 27° 30" 4,812 10-inch Columbiad 39° 15" 5,654 12-inch Columbiad 39° 0" 5,506

Ranges of United States naval smoothbores of 1866 Caliber Point-blank

range in yardsElevation Range in yards 32-pounder of 42 cwt 313 5° 1,756 8-inch of 63 cwt 330 5° 1,770 IX-inch shell gun 350 15° 3,450 X-inch shell gun 340 11° 3,000 XI-inch shell gun 295 15° 2,650 XV-inch shell gun 300 7° 2,100

Ranges of United States naval rifles in 1866 Caliber Elevation Range in yards 20-pounder Parrott 15° 4,400 30-pounder Parrott 25° 6,700 100-pounder Parrott 25° 7,180 In accuracy and range the rifle of the 1860's far surpassed the smoothbores, but such tremendous advances were made in the next few decades with the introduction of new propellants and steel guns that the performances of the old rifles no longer seem remarkable.

In the eighteenth century, a 24-pounder smoothbore could develop a muzzle velocity of about 1,700 feet per second. The 12-inch rifled cannon of the late 1800's had a muzzle velocity of 2,300 foot-seconds. In 1900, the Secretary of the Navy proudly reported that the new 12-inch guns for Maine-class battleships produced a muzzle velocity of 2,854 foot-seconds, using an 850-pound projectile and a charge of 360 pounds of smokeless powder. Such statistics elicit a chuckle from today's artilleryman.

-

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on February 18, 2011 at 3:52pm

-

Standard Deck Cannon

As you can see the weight of the cannon had to significantly increase as the size of the shot increased. However the weight ratio of powder to shot decreases as the shot gets larger. Most of the weight of the gun is centered around the breech of the gun where the explosion takes place and most of the pressure is exerted. Guns wore out relatively fast, usually being good for 500 to 1,000 shots before being rendered unsafe to use anymore.

Cannons of the Seventeenth Century

The main changes in the 17th century involved sizes and numbers. European ships were now carrying as many as 100 guns on three separate decks. 42 pounder guns were often the standard gun on the bottom decks. Special shots or artillery rounds were being developed especially for naval use. Barshot, chain shot, were rounds designed to destroy rigging and sails. Bundle shot, canister, grape shot were used against personnel. Cluster rounds and Sangrenel rounded out the variety of shots fired from the Cannon. (See below for a fuller treatment)Cannons of the Eighteenth Century

Ships of War had improved dramatically by the opening of the 18th Century, In fact, the Golden Age of Piracy was probably the Golden Age of Sail as well. Cast Iron muzzle loaders ranging from the small 6 pounders to the large 32 pounders were the general rule. Elevation was adjusted by a modified quoin under the breech and the general science of trajectory was better understood. Fixed loads of powder were calculated for the guns improving accuracy and the guns were secured to the sides of the ships by heavy breech ropes passed through or around the casabels, limiting recoil and aiding in the reloading of the guns. Side tackles were also added as well as small ramps behind the guns to aid in pulling them back into firing position.The Naval Artillery had unheard of range of about 2,000 yards (meters) by this time. Of course most engagements were fought at under 1,000 yards and sometimes within pistol shot (25 to 50 yards) The only innovation in artillery rounds for this time period was the art of heating solid iron shot to a red hot condition before firing the round. It was a tricky affair, because the heat of the hot iron could cause a cook off, that is an early discharge of the cannon, thus killing your own cannoneers. The usual method for firing red hot iron was to swab the barrel with water then dry the inside, add the powder, followed by a plug of wood and then the loose fitting hot iron. The purpose of using the hot iron was to set the other ship on fire.

The art of explosive shells also came of age. An explosive cannon ball fitted with a timed fuse would be fired from the gun. If the timing was done properly, the shell would explode when it reached the other ship. Some of the cannons began using a flintlock mechanism for firing instead of the flaming torch that is used in so many movies. The torch could be used but the flintlock was more reliable and much safer. The mechanism worked by pulling a lanyard instead of a trigger.

The term "pounder" refers to the size of a gun. A six pounder fired a solid shot of lead which weighed approximately 6 pounds. A 32 pounder fired a ball of lead that weighed approximately 32 pounds. Although this makes the identification of a cannon's power very simple, it says little about the approximate weight of the cast iron gun. For Instance:

Type

Bore Size

Gun Weight

Shot Weight

2 Pounder

2.5 Inch

600 lbs

2 pounds

3.5 pounds

6 Pounder

3.0 Inch

1,000-1,500

6 pounds

6 pounds

24 Pounder

4.5 Inch

3,000-4,000

24 pounds

14 pounds

32 Pounder

5.0 Inch

4,000-5,000

32 pounds

18 pounds

-

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on February 18, 2011 at 3:52pm

-

Swivel Cannon

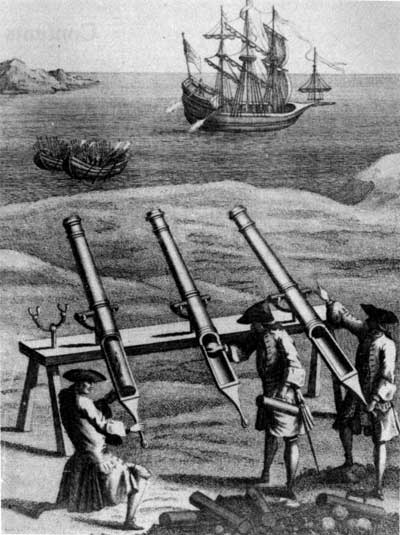

A swivel gun is a small cannon, mounted on a swiveling stand or fork which allows a very wide arc of movement. Such weapons were used principally aboard sailing ships during the age of sail, serving as short-range anti-personnel ordnance. They were not ship-sinking weapons, due to their small caliber and short range, but could do considerable damage to anyone caught in their line of fire.

A swivel gun is a small cannon, mounted on a swiveling stand or fork which allows a very wide arc of movement. Such weapons were used principally aboard sailing ships during the age of sail, serving as short-range anti-personnel ordnance. They were not ship-sinking weapons, due to their small caliber and short range, but could do considerable damage to anyone caught in their line of fire.Swivel guns are among the smallest types of cannon, typically measuring less than 1 m (3 ft) in length and with a bore diameter of up to 3.5 cm (1¼ in). They can fire a variety of ammunition but were generally used to fire grapeshot and similar types of small-diameter shot, though they could also fire small caliber round shot. As with other types of cannon, swivel guns are muzzleloaders. They were aimed through the use of a wooden handle, somewhat similar to a baseball bat, attached to the breech of the weapon.

In operational use, swivel guns were highly portable and could be moved around the deck of a ship quite easily (and certainly much more easily than other types of cannon). They could be mounted on the deck railings of a ship, which provided the gunner with a reasonably steady platform from which to fire. Their portability enabled them to be installed wherever they were most needed; whereas larger cannon were useless if they were on the wrong side of the ship, swivel guns could be carried across the deck to face the enemy.

"PIERIERS VULGARLY CALLED PATTEREROS,"

from Francis Grose, Military Antiquities, 1796 -

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on February 18, 2011 at 3:52pm

-

Siege Cannons

Heavy siege guns were elevated with quoins, and elevation was restricted to 12° or less, which was about the same as United States siege carriages permitted in 1861. It was considered ample for these flat trajectory pieces.

Both field and siege carriages were pulled over long distances by lifting the trail to a horse- or ox-drawn limber; a hole in the trail transom seated on an iron bolt or pintle on the two-wheeled limber. Some late eighteenth century field and siege carriages had a second pair of trunnion holes a couple of feet back from the regular holes, and the cannon was shifted to the rear holes where the weight was better distributed for traveling. The United States siege carriage of the 1860's had no extra trunnion holes, but a "traveling beds" was provided where the gun was cradled in position 2 or 3 feet back of its firing position. A well-drilled gun crew could make the shift very rapidly, using a lifting jack, a few rollers, blocks, and chocks. When there was danger of straining or breaking the gun carriage, however, massive block carriages, sling carts, or wagons were used to carry the guns.

Sling wagons were of necessity used for transport in siege operations when the guns were to be mounted on barbette (traversing platform) carriages (fig. 10). Emplacing the barbette carriage called for construction of a massive, level subplatform, but it also eliminated the old need for the gunner to chalk the location of his wheels in order to return his gun to the proper firing position after each shot.

The Federal sieges of Forts Pulaski and Sumter were highly complicated engineering operations that involved landing tremendously heavy ordnance (the 300-pounder Parrott weighed 13 tons) through the surf, moving the big guns over very difficult terrain and, in some cases, building roads over the marshes and driving foundation piles for the gun emplacements.

The heavy caliber Parrotts trained on Fort Sumter were in batteries from 1,750 to 4,290 yards distant from their target. They were very accurate, but their endurance was an uncertain factor. The notorious "Swamp Angel," for instance, burst after 36 rounds.

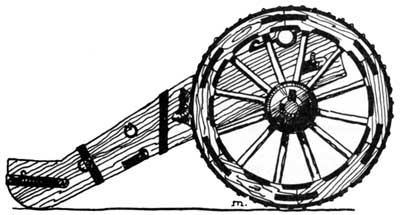

Field counterpart of the garrison cannon was the siege gun—the "battering cannon" of the old days, mounted upon a two-wheeled siege or "traveling" carriage that could be moved about in field terrain. Whereas the purpose of the garrison cannon was to destroy the attacker and his materiel, the siege cannon was intended to destroy the fort. Calibers ranged from 3- to 42-pounders in eighteenth century British tables, but the 18- and 24-pounders seem to have been the most widely used for siege operations.

FIGURE 32—SPANISH EIGHTEENTH CENTURY SIEGE CARRIAGE.The siege carriage closely resembled the field gun carriage, but was much more massive, as may be seen from these comparative figures drawn from eighteenth century British specifications:

24-pounder field carriage

24-pounder siege carriage 9 feet long Length of cheek 13 feet. 4.5 inches Thickness of cheek 5.8 inches. 50 inches Wheel diameter 58 inches. 6x8x68 inches Axletree 7x9x81 inches. -

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on February 18, 2011 at 3:53pm

-

Field Cannon

Amazingly enough, these ranges were obtained with about the same amount of powder used for the smoothbores of similar caliber: the 10-pounder Parrott used only a pound of powder; the 20-pounder used a two-pound charge; and the 30-pounder, 3-1/4 pounds!

The field guns were the mobile pieces that could travel with the army and be brought quickly into firing position. They were lighter in weight than any other type of flat trajectory weapon. To achieve this lightness the designers had not only shortened the guns, but thinned down the bore walls. In the eighteenth century, calibers ran from the 3- to the 24-pounder, mounted on comparatively light, two-wheeled carriages. In addition, there was the 1-1/2-pounder (and sometimes the light 3- or 6-pounder) on a "gallopers' carriage—a vehicle with its trail shaped into shafts for the horse. The elevating-screw mechanism was early developed for field guns, although the heavier pieces like the 18- and 24-pounders were still elevated by quoins as late as the early 1800's.

FIGURE 33—SPANISH 4-POUNDER FIELD CARRIAGE (c. 1788). This carriage, designed on the "new method," employed a handscrew instead of a wedge for elevating the piece. a—The handspike was inserted through eye-bolts in the trail. b—The ammunition locker held the cartridges.In the Castillo collection are parts of early United States field carriages little different from Spanish carriages that held a score of 4-pounders in the long, continuous earthwork parapet surrounding St. Augustine in the eighteenth century. The Spanish mounts were a little more complicated in construction than British or American carriages, but not much. Spanish pyramid-headed nails for securing ironwork were not far different from the diamond- and rose-headed nails of the British artificer.

Each piece of hardware on the carriage had its purpose. Gunner's tools were laid in hooks on the cheeks, There were bolts and rings for the lines when the gun had to be moved by manpower in the field. On the trail transom, pintle plates rimmed the hole that went over the pintle on the limber. Iron reinforced the carriage at weak points or where the wood was subject to wear. Iron axletrees were common by the late 1700's.

For training the field gun, the crew used a special handspike quite different from the garrison handspike. It was a long, round staff, with an iron handle bolted to its head (fig. 33a). The trail transom of the carriage held two eyebolts, into which the foot of the spike was inserted. A lug fitted into an offset in the larger eyebolt so that the spike could not twist. With the handspike socketed in the eyebolts, lifting the trail and laying the gun was easy.

The single-trail carriage (fig. 13) used so much during the middle 1800's was a remarkable simplification of carriage design. It was also essential for guns like the Parrott rifles, since the thick reinforce on the breech of an otherwise slender barrel would not fit the older twin-trail carriage. The single, solid "stock" or trail eliminated transoms, for to the sides of the stock itself were bolted short, high cheeks, humped like a camel to cradle the gun so high that great latitude in elevation was possible. The elevating screw was threaded through a nut in the stocks under the big reinforce of the gun.

While the larger bore siege Parrotts were not noted for long serviceability, Parrott field rifles had very high endurance. As for performance, see the following table:

Ranges of Parrott field rifles (1863) Caliber Weight

of guns

(pounds)Type of

projectileProjectile

weighs

(pounds)Elevation Range

(yards)Smoothbore

of same

caliber10-pounder 890 Shell

..do..9.75

9.755°

20°2,000

5,0003-pounder. 20-pounder 1,750 ..do..

..do..18.75

18.755°

15°2,100

4,4406-pounder. 30-pounder 4,200 ..do..

..do..

Long shell.

..do..

Hollow shot.

..do..29.00

29.00

101.00

101.00

80.00

80.0015°

25°

15°

25°

25°

35°4,800

6,700

4,790

6,820

7,180

8,4539-pounder. -

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on February 18, 2011 at 3:54pm

-

Cannon - Howitzers

The howitzer was invented by the Dutch in the seventeenth century to throw larger projectiles (usually bombs) than could the field pieces, in a high trajectory similar to the mortar, but from a lighter and more mobile weapon. The wide-purpose efficiency of the howitzer was appreciated al most at once, and it was soon adopted by all European armies. The weapon owed its mobility to a rugged, two-wheeled carriage like a field carriage, but with a relatively short trail that permitted the wide arc of elevation needed for this weapon.

FIGURE 34—SPANISH 6-INCH HOWITZER (1759-88). This bronze piece was founded during the reign of Charles III and bears his shield, a—Dolphin, or handle, b—Bore, c—Powder chamber.British howitzers of the 1750's were of three calibers: 5.8-, 8-, and 10-inch, but the 10-incher was so heavy (some 50 inches long and over 3,500 pounds) that it was quickly discarded. Müller deplored the superfluous weight of these pieces and developed 6-, 8-, 10-, and 13-inch howitzers in which, by a more calculated distribution of the metal, he achieved much lighter weapons. Müller's howitzers survived in the early 6- to 10-inch pieces of United States artillery and one fine little 24-pounder of the late eighteenth century happens to be among the armament of Castillo de San Marcos, along with some early nineteenth century howitzers. The British, incidentally, were the first to bring this type gun to Florida. None appeared on the Castillo inventory until the 1760's.

FIGURE 35—ENGLISH 8-INCH "HOWITZ" CARRIAGE (1756). The short trail enabled greater latitude in elevating the howitzer.In addition to the very light and therefore easily portable mountain howitzer used for Indian warfare, United States artillery of 1850 included 12-, 24-, and 32-pounder field, 24-pounder and 8-inch siege and garrison, and the 10-inch seacoast howitzer. The Navy had a 1 2-pounder heavy and a 24-pounder, to which were added the 12- and 24-pounder Dahlgren rifled boat howitzers of the Civil War period. Such guns were often used in landing operations. The following table gives some typical ranges:

Ranges of U. S. Howitzers in the 1860's Caliber Elevation Range in yards 10-inch seacoast 5° 1,650 8-inch siege 12° 30" 2,280 24-pounder naval 5° 1,270 12-pounder heavy naval 5° 1,085 20-pounder Dahlgren rifled 5° 1,960 12-pounder Dahlgren rifled 5° 1,770 -

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on February 18, 2011 at 3:54pm

-

Mortars

At the siege of Fort Pulaski in 1862, however, General Gillmore complained that the mortars were highly inaccurate at mile-long range. On this point, John Müller would have nodded his head emphatically. A hundred years before Gillmore's complaint, Müller had argued that a range of something less than 1,500 yards was ample for mortars or, for that matter, all guns. "When the ranges are greater," said Müller, "they are so uncertain, and it is so difficult to judge how far the shell falls short, or exceeds the distance of the object, that it serves to no other purpose than to throw away the Powder and shell, without being able to do any execution."

From earliest times the usefulness of the mortar as an arm of the artillery has been clearly recognized. Up until the 1800's the weapon was usually made of bronze, and many mortars had a fixed elevation of 45°, which in the sixteenth century was thought to be the proper elevation for maximum range of any cannon. In the 1750's Müller complained of the stupidity of British artillerists in continuing to use fixed-elevation mortars, and the Spanish made a mortero de plancha, or "plate" mortar (fig. 37), as late as 1788. Range for such a fixed-elevation weapon was varied by using more or less powder, as the case required. But the most useful mortar, of course, had trunnions and adjustable elevation by means of quoins.

FIGURE 36—BRITISH MORTAR ON ELEVATING BED (1740).The mortar was mounted on a "bed"—a pair of wooden cheeks held together by transoms. Since a bed had no wheels, the piece was transported on a mortar wagon or sling cart. In the battery, the mortar was generally bedded upon a level wooden platform; aboard ship, it was a revolving platform, so that the piece could be quickly aimed right or left. The mortar's weight, plus the high angle of elevation, kept it pretty well in place when it was fired, although British artillerists took the additional precaution of lashing it down.

FIGURE 37—SPANISH 5-INCH BRONZE MORTAR (1788).The mortar did not use a wad, because a wad prevented the fuze of the shell from igniting. To the layman, it may seem strange that the shell was never loaded with the fuze toward the powder charge of the gun. But the fuze was always toward the muzzle and away from the blast, a practice which dated from the early days when mortars were discharged by "double firing": the gunner lit the fuze of the shell with one hand and the priming of the mortar with the other. Not until the late 1600's did the method of letting the powder blast ignite the fuze become general. It was a change that greatly simplified the use of the arm and, no doubt, caused the mortarman to heave a sigh of relief.

FIGURE 38—SPANISH 10-INCH BRONZE MORTAR (1759-88). a—Dolphin, or handle, b—Bore, c—Powder chamber.Most mortars were equipped with dolphins, either singly or in pairs, which were used for lifting the weapon onto its bed. Often there was a little bracketed cup—a priming pan—under the vent, a handy gadget that saved spilling a lot of powder at the almost vertical breech. As with other bronze cannon, mortars were embellished with shields, scrolls, names, and other decoration.

About 1750, the French mortar had a bore length 1-1/2 diameters of the shell; in England, the bore was 2 diameters for the smaller calibers and 3 for the 10- and 13-inchers. The extra length added a great deal of weight to the British mortars: the 13-inch weighed 25 hundredweight, while the French equivalent weighed only about half that much. Müller complained that mortar designers slavishly copied what they saw in other guns. For instance, he said, the reinforce was unnecessary; it . . . overloads the Mortar with a heap of useless metal, and that in a place where the least strength is required, yet as if this unnecessary metal was not sufficient, they add a great projection at the mouth, which serves to no other purpose than to make the Mortar top-heavy. The mouldings are likewise jumbled together, without any taste or method, tho' they are taken from architecture." Field mortars in use during Müller's time included 4.6-, 5.8-, 8-, 10-, and 13-inch "land" mortars and 10- and 13-inch "sea" mortars. Muller, of course, redesigned them.

FIGURE 39—COEHORN MORTAR. The British General Oglethorpe used 20 coehorns in his 1740 bombardment of St. Augustine. These small mortars were also used extensively during the Civil War.The small mortars called coehorns (fig. 39) were invented by the famed Dutch military engineer, Baron van Menno Coehoorn, and used by him in 1673 to the great discomfit of French garrisons. James Oglethorpe had many of them in his 1740 bombardment of St. Augustine when the Spanish, trying to translate coehorn into their own tongue, called them cuernos de vaca—"cow horns." They continued in use through the U.S. Civil War, and some of them may still be seen in the battlefield parks today.

Bombs and carcasses were usual for mortar firing, but stone projectiles remained in use as late as 1800 for the pedrero class (fig. 43). Mortar projectiles were quite formidable; even in the sixteenth century missiles weighing 100 or more pounds were not uncommon, and the 13-inch mortar of 1860 fired a 200-pound shell. The larger projectiles had to be whipped up to the muzzle with block and tackle.

FIGURE 40—THE "DICTATOR." This huge 13-inch mortar was used by the Federal artillery in the bombardment of Petersburg, Va., 1864-65.In the last century, the bronze mortars metamorphosed into the great cast-iron mortars, such as "The Dictator," that mammoth Federal piece used against Petersburg, Va. Wrought-iron beds with a pair of rollers were built for them. In spite of their high trajectory, mortars could range well over a mile, as witness these figures for United States mortars of the 1860's, firing at 45° elevation:

Ranges of U. S. Mortars in 1861 Caliber Projectile

weight (pounds)Range

(yards)8-inch siege 45 1,837 10-inch siege 90 4,625 12-inch seacoast 200 2,100 13-inch seacoast 200 4,325 -

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on February 18, 2011 at 3:54pm

-

Petards

"Hoist with his own petard," an ancient phrase signifying that one's carefully laid scheme has exploded, had truly graphic meaning in the old days when everybody knew what a petard was. Since the petard fired no projectile, it was hardly a gun. Roughly speaking, it was nothing but an iron bucket full of gunpowder. The petardier would hang it on a gate, something like hanging your hat on a nail, and blast the gate open by firing the charge.

Small petards weighed about 50 pounds; the large ones, around 70 pounds. They had to be heavy enough to be effective, yet light enough for a couple of men to lift up handily and hang on the target. The bucket part was packed full of the powder mixture, then a 2-1/2-inch-thick board was bolted to the rim in order to keep the powder in and the air out. An iron tube fuze was screwed into a small hole in the back or side of the weapon. When all was ready, the petardiers seized the two handles of the petard and carried it to the troublesome door. Here they set a screw, hung the explosive instrument upon it, lit the fuze, and "retired."

Petards were used frequently in King William's War of the 1680's to force the gates of small German towns. But on a well-barred, double gate the small petard was useless, and the great petard would break only the fore part of such a gate. Furthermore, as one would guess, hanging a petard was a hazardous occupation; it went out of style in the early 1700's.

-

Events

-

2014 is the Chinese Year of the Horse

February 17, 2026 at 12am to February 5, 2027 at 12am – where & how you choose

Birthdays

Birthdays Today

Birthdays Tomorrow

Important (read & understand)

Skype: Travelingraggyman

Email and Instant Messenger:

TravelerinBDFSM @ aol/aim; hotmail; identi.ca; live & yahoo

OR

Travelingraggyman @ gmail and icq ***

1AWARD UPDATES & INFORMATION

10,000 votes - Platinum Award

5,000 votes - Gold Award

2,500 votes - Silver Award

1,000 votes - Bronze Award

300 votes - Pewter Award

100 votes - Copper Award

Member of the Associated Posting System {APS}

This allows members on various sites to share information between sites and by providing a by line with the original source it credits the author with the creation.

Legal Disclaimer

***************We here at Traveling within the World are not responsible for anything posted by individual members. While the actions of one member do not reflect the intentions of the entire social network or the Network Creator, we do ask that you use good judgment when posting. If something is considered to be inappropriate it will be removed

Site Meter

This site is strictly an artist operational fan publication, no copyright infringement intended

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries had its humble beginnings as an idea of a few artisans and craftsmen who enjoy performing with live steel fighting. As well as a patchwork quilt tent canvas. Most had prior military experience hence the name.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries.

Vendertainers that brought many things to a show and are know for helping out where ever they can.

As well as being a place where the older hand made items could be found made by them and enjoyed by all.

We expanded over the years to become well known at what we do. Now we represent over 100 artisans and craftsman that are well known in their venues and some just starting out. Some of their works have been premiered in TV, stage and movies on a regular basis.

Specializing in Medieval, Goth , Stage Film, BDFSM and Practitioner.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries a Dept of, Ask For IT was started by artists and former military veterans, and sword fighters, representing over 100 artisans, one who made his living traveling from fair to festival vending medieval wares. The majority of his customers are re-enactors, SCAdians and the like, looking to build their kit with period clothing, feast gear, adornments, etc.

Likewise, it is typical for these history-lovers to peruse the tent (aka mobile store front) and, upon finding something that pleases the eye, ask "Is this period?"

A deceitful query!! This is not a yes or no question. One must have a damn good understanding of European history (at least) from the fall of Rome to the mid-1600's to properly answer. Taking into account, also, the culture in which the querent is dressed is vitally important. You see, though it may be well within medieval period, it would be strange to see a Viking wearing a Caftan...or is it?

After a festival's time of answering weighty questions such as these, I'd sleep like a log! Only a mad man could possibly remember the place and time for each piece of kitchen ware, weaponry, cloth, and chain within a span of 1,000 years!! Surely there must be an easier way, a place where he could post all this knowledge...

Traveling Within The World is meant to be such a place. A place for all of these artists to keep in touch and directly interact with their fellow geeks and re-enactment hobbyists, their clientele.

© 2025 Created by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler.

Powered by

![]()