Traveling within the World

Linking your favorite traveling artists across the globe

I can do this for you. It will take cost of materials and time to do so. But the question to start with is which version of time period do you want them of?

Look here http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Runes this will show you the time periods and styles.

Will make of wood burned within with a period finished style to weather protect them. round or oval angle cut?

This could just as well go into You want what?

he runic alphabets are a set of related alphabets using (alphabet)"">letters known as runes to write various Germanic languages prior to the adoption

of the alphabet"">Latin alphabet and for specialized purposes thereafter.

The Scandinavian variants are also known as futhark (or fuþark,

derived from their first six letters of the alphabet: F,

U,

(letter)"">Þ, A, R,

and K); the Anglo-Saxon

variant is futhorc (due to sound changes undergone in Old English by the same six letters). Runology is the study of the runic alphabets, runic inscriptions, runestones, and their

history. Runology forms a specialized branch of linguistics" class="mw-redirect"">Germanic linguistics.

The earliest runic inscriptions date from around A.D. 150. The characters were generally replaced by the alphabet"">Latin alphabet as the cultures that had used runes

underwent Christianization by around A.D. 700 in

central Europe and by around A.D. 1100 in Europe"">Northern Europe. However, the use of runes persisted for

specialized purposes in Northern Europe. Until the early twentieth

century runes were used in rural Sweden for

decoration purposes in Dalarna

and on calendar"">Runic calendars).

The three best-known runic alphabets are the Elder Futhark (around 150 to 800 AD), the English language" class="mw-redirect"">Old English Futhorc (400 to 1100 AD), and the Younger Futhark (800–1100). The Younger

Futhark is further divided into the long-branch runes (also called Danish,

although they were also used in Norway and Sweden), short-branch or Rök runes (also called Swedish-Norwegian,

although they were also used in Denmark), and the stavesyle or Hälsinge

runes (runes"">staveless runes). The Younger Futhark developed further into

the Marcomannic runes, the runes"">Medieval runes (1100 AD to 1500 AD), and the Dalecarlian runes (around 1500 to 1800 AD).

The origins of the runic alphabet are uncertain. Many characters of the Elder Futhark bear a close resemblance to characters from the Latin

alphabet. Other candidates are the 5th to 1st century BC Northern Italic

alphabets: Lepontic, language" class="mw-redirect"">Rhaetic and language"">Venetic, all of which are closely related to each other

and descend from the Italic alphabet"">Old Italic alphabet.

History and usage

runes, the Elder

Futhark and the Futhark"">Younger Futhark, on the 9th century Runestone"">Rök Runestone in Sweden.

The runes were in use among the Germanic peoples from the 1st or 2nd

century AD.[1]

This period corresponds to the late Germanic" class="mw-redirect"">Common Germanic stage linguistically,

with a continuum of dialects not yet clearly separated into the three

branches of later centuries; Germanic" class="mw-redirect"">North Germanic, West Germanic, and East Germanic.

No distinction is made in surviving runic inscriptions between long and short vowels, although such a distinction was certainly present

phonologically in the spoken languages of the time. Similarly, there are

no signs for labiovelars in the Elder Futhark (such signs

were introduced in both the Anglo-Saxon futhorc and the alphabet"">Gothic alphabet as variants of p; see peorð.)

The name runes contrasts with Latin or Greek letters. It is attested on a 6th century Alamannic

runestaff as runa, and possibly as runo on the 4th

century Einang

stone. The name is from a root run- (Gothic runa),

meaning "secret" or "whisper". The root run- can also be found in

the Baltic languages meaning "speech". In Lithuanian, runoti has

two meanings: "to cut (with a knife)" or "to speak".[2]

[edit] Origins

The runes developed centuries after the Old Italic alphabets from

which they are historically derived. The debate on the development of

the runic script concerns the question which of the Italic alphabets

should be taken as their point of origin, and which, if any, signs

should be considered original innovations added to the letters found in

the Italic scripts. The historical context of the script's origin is the

cultural contact between Germanic people, who often served as mercenaries in the auxiliaries" class="mw-redirect"">Roman army, and the Italic

peninsula during the Roman

imperial period (1st c. BC to 5th c. AD). The formation of the

Elder Futhark was complete by the early 5th century, with the Kylver Stone being the first evidence of the futhark

ordering as well as of the p rune.

Specifically, the Raetic alphabet of Bolzano,

is often advanced as a candidate for the origin of the runes, with only

five Elder Futhark runes ( ᛖ e,

ᛇ ï,

ᛃ j,

ᛜ ŋ,

ᛈ p)

having no counterpart in the Bolzano alphabet (Mees 2000). Scandinavian

scholars tend to favor derivation from the alphabet"">Latin alphabet itself over Raetic candidates.[3]

A "North Etruscan" thesis is supported by the inscription on the Negau helmet dating to the 2nd century BC[4]

This is in a northern Etruscan alphabet, but features a Germanic name, Harigast.

New archaeological evidence came from Monte Calvario (Auronzo di

Cadore).

The angular shapes of the runes are shared with most contemporary alphabets of the period used for carving in wood or stone. A peculiarity

of the runic alphabet is the absence of horizontal strokes,

although this characteristic is also shared by other alphabets, such as

the early form of the alphabet"">Latin alphabet used for the inscription" class="mw-redirect"">Duenos inscription, and it is not

universal especially among early runic inscriptions, which frequently

have variant rune shapes including horizontal strokes.

The "West Germanic hypothesis" speculates on an introduction by Germanic tribes"">West Germanic tribes. This hypothesis is based on

claiming that the earliest inscriptions of around 200 AD, found in bogs

and graves around Jutland (the inscriptions"">Vimose inscriptions), exhibit word endings that, being

interpreted by Scandinavian

scholars to be Proto-Norse,

are considered unresolved and having been long the subject of

discussion. Inscriptions like wagnija, niþijo, and harija

are supposed to incarnate tribe names, tentatively proposed to be Vangiones, the Nidensis and the

Harii, tribes located in the Rhineland.[5]

Since names ending in -io reflect Germanic morphology

representing the Latin ending -ius, and the suffix -inius

was reflected by Germanic -inio-,[6]

the question of the problematic ending -ijo in masculine

Proto-Norse would be resolved by assuming Roman (Rhineland) influences,

while "the awkward ending -a of laguþewa (cf. Syrett 1994:44f.) can be

solved by accepting the fact that the name may indeed be West Germanic;"[7]

however, it should be noted that in the early Runic period differences

between Germanic languages are generally assumed to be small. Another

theory assumes a Germanic"">Northwest Germanic unity preceding the emergence of

Proto-Norse proper from roughly the 5th century.[8]

An alternative suggestion explaining the impossibility to classify the

earliest inscriptions as either North or West Germanic is forwarded by

È. A. Makaev, who assumes a "special runic koine", an early "literary Germanic" employed by

the entire Late Common Germanic linguistic community after the

separation of Gothic (2nd to 5th centuries), while the spoken dialects

may already have been more diverse.[9]

[edit] Early inscriptions

Trenk, 1875.

Runic inscriptions from the 400 year period of c. 150 to 550 AD are referred to as "Period I" inscriptions. These inscriptions are generally

in Elder Futhark, but the set of letter shapes

and bindrunes employed is far from

standardized. Notably the j, s and ŋ runes undergo considerable modifications,

while others, such as p and ï, remain unattested altogether prior the

first full futhark row on the Kylver

Stone (ca. 400 AD).

Theories of the existence of separate Gothic runes have been advanced, even identifying them as

the original alphabet from which the Futhark were derived, but these

have little support in actual findings (mainly the of Kovel" class="mw-redirect"">spearhead of Kovel, with its

right-to-left inscription, its T-shaped tiwaz

and its rectangular dagaz). If

there ever were genuinely Gothic runes, they were soon replaced by the Gothic alphabet. The letters of the Gothic

alphabet, however, as given by the Alcuin

manuscript (9th century), are obviously related to the names of the

Futhark. The names are clearly Gothic, but it is impossible to say

whether they are as old as, or even older than, the letters themselves. A

handful of Elder Futhark inscriptions were found in Gothic territory,

such as the 3rd to 5th century Pietroassa"">Ring of Pietroassa.

[edit] Magical or divinatory use

inscription but the charm word alu

with a depiction of a stylized male head, horse and a swastika, a common motif on bracteates.

In stanza 157 of Hávamál, the runes are attributed with the power to bring that which is dead to life. In this stanza, Odin recounts a spell:

|

|

The earliest runic inscriptions found on artifacts give the name of either the craftsman or the proprietor, or, sometimes, remain a

linguistic mystery. Due to this, it is possible that the early runes

were not so much used as a simple writing system, but rather as (paranormal)"">magical signs to be used for charms. Although some say

the runes were used for divination,

there is no direct evidence to suggest they were ever used in this way.

The name rune itself, taken to mean "secret, something hidden",

seems to indicate that knowledge of the runes was originally considered

esoteric, or restricted to an elite. The 6th century Björketorp Runestone warns in Proto-Norse using

the word rune in both senses:

Haidzruno runu, falahak haidera, ginnarunaz. Arageu haeramalausz uti az. Weladaude, sa'z þat barutz. Uþarba spa.

I, master of the runes(?) conceal here runes of power. Incessantly (plagued by) maleficence, (doomed to) insidious death (is) he who breaks this (monument). I prophesy destruction / prophecy of destruction.[12]

The same curse and use of the word rune is also found on the Stentoften Runestone. There are also some inscriptions suggesting a medieval belief in the magical

significance of runes, such as the Franks

Casket (700 AD) panel.

Charm words, such as auja, laþu, laukaR and most commonly, alu,[13]

appear on a number of period"">Migration period Elder Futhark inscriptions as well as

variants and abbreviations of them. Much speculation and study has been

produced on the potential meaning of these inscriptions. Rhyming groups

appear on some early bracteates that may also be magic in purpose, such

as salusalu and luwatuwa. Further, an inscription on the Gummarp Runestone (500 to 700 AD) gives a

cryptic inscription describing the use of three runic letters followed

by the Elder Futhark f-rune written three times in succession.[14]

Nevertheless, it has proven difficult to find unambiguous traces of runic "oracles": Although language" class="mw-redirect"">Norse literature is full of references

to runes, it nowhere contains specific instructions on divination.

There are at least three sources on divination with rather vague

descriptions that may or may not refer to runes: Tacitus's

1st century (book)"">Germania, Snorri Sturluson's 13th century Ynglinga saga and Rimbert's

9th century Vita

Ansgari.

The first source, Tacitus's Germania, describes "signs" chosen in groups of three and cut from "a nut-bearing tree," although the

runes do not seem to have been in use at the time of Tacitus' writings. A

second source is the Ynglinga saga, where Granmar,

the king of Södermanland, goes to Uppsala

for the blót.

There, the "chips" fell in a way that said that he would not live long (Féll

honum þá svo spánn sem hann mundi eigi lengi lifa). These "chips,"

however, are easily explainable as a blótspánn (sacrificial

chip), which was "marked, possibly with sacrificial blood, shaken and

thrown down like dice, and their positive or negative significance then

decided."[15]

The third source is Rimbert's Vita Ansgari, where there are three accounts of what some believe to be the use of runes for

divination, but Rimbert calls it "drawing lots". One of these accounts

is the description of how a renegade Swedish king Anund

Uppsale first brings a Danish fleet to Birka, but

then changes his mind and asks the Danes to "draw lots". According to

the story, this "drawing of lots" was quite informative, telling them

that attacking Birka would bring bad luck and that they should attack a

Slavic town instead. The tool in the "drawing of lots," however, is

easily explainable as a hlautlein (lot-twig), which according to

Foote and Wilson[15]

would be used in the same manner as a blótspánn.

The lack of extensive knowledge on historical usage of the runes has not stopped modern authors from extrapolating entire systems of

divination from what few specifics exist, usually loosely based on the

runes' reconstructed names and additional outside influence.

A recent study of runic magic suggests that runes were used to create magical objects such as amulets (MacLeod and Mees 2006), but not in a

way that would indicate that runic writing was any more inherently

magical than were other writing systems such as Latin or Greek.

[edit] Medieval use

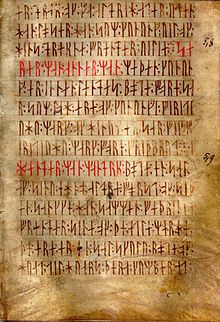

1300 AD containing one of the oldest and best preserved texts of the Scanian Law, written entirely in runes.

As Proto-Germanic evolved into its later language groups, the words assigned to the runes and the sounds represented by the runes themselves

began to diverge somewhat, and each culture would either create new

runes, rename or rearrange its rune names slightly, or even stop using

obsolete runes completely, to accommodate these changes. Thus, the

Anglo-Saxon futhorc has several runes peculiar to itself to represent diphthongs unique to (or at least prevalent in)

the Anglo-Saxon dialect.

Nevertheless, the fact that the Younger Futhark has 16 runes, while the Elder Futhark has 24, is not fully explained by the some 600 years

of sound changes that had occurred in the Germanic" class="mw-redirect"">North Germanic language group. The

development here might seem rather astonishing, since the younger form

of the alphabet came to use fewer different rune signs at the same time

as the development of the language led to a greater number of different

phonemes than had been present at the time of the older futhark. For

example, voiced and unvoiced consonants merged in script, and so did

many vowels, while the number of vowels in the spoken language

increased. From about 1100, this disadvantage was eliminated in the

medieval runes, which again increased the number of different signs to

correspond with the number of phonemes in the language.

Some later runic finds are on monuments (runestones), which often contain solemn inscriptions about people who died or

performed great deeds. For a long time it was assumed that this kind of

grand inscription was the primary use of runes, and that their use was

associated with a certain societal class of rune carvers.

In the mid-1950s, however, about 600 inscriptions known as the Bryggen inscriptions were found in Bergen. These inscriptions were made on wood and bone, often in the shape of sticks of

various sizes, and contained inscriptions of an everyday nature—ranging

from name tags, prayers (often in Latin),

personal messages, business letters and expressions of affection to

bawdy phrases of a profane and sometimes even vulgar nature. Following

this find, it is nowadays commonly assumed that at least in late use,

Runic was a widespread and common writing system.

In the later Middle Ages, runes were also used in the Clog almanacs (sometimes called Runic staff, Prim or Scandinavian calendar) of Sweden and

Estonia. The authenticity of some monuments bearing Runic inscriptions

found in Northern America is disputed, but most of them date from modern

times.

Tags:

Replies to This Discussion

-

Permalink Reply by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler on April 20, 2010 at 4:07pm

-

ok, I want Elder Futhark round angle. Can you tell me the price and the way to pay ?

I will have to go price out materials and give you also the sizes I can do this in. As far as payment it will be either US money order or directly using a charge card to pay for the site to live. S/H&I should not be that much I will need an address to figure that out as well.

Are these you ask of correct?

-

-

Permalink Reply by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler on April 20, 2010 at 4:38pm

-

Priority Mail® International Small Flat Rate Box

8 5/8" x 5 3/8" x 1 5/8". Maximum weight 4 pounds.

Priority Mail® International Small Flat Rate Box*

Speed 6 - 10 Days

Post Office Price $13.45 -

-

Permalink Reply by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler on April 20, 2010 at 4:45pm

-

The wood I will be using is either ash or hickory. For as the olden ways the runes were made from the shafts of the broken weapons. These were usually of hickory or ash woods.

A tree is the most perfect of spiritual beings, with its roots buried alive in Mother Earth and its limbs alive and growing in Father Sky.

According to the Song of the Sybil, when the earth was young, Odin and his two brothers found two trees: an ash tree and an elm, faint, feeble, with no fate assigned to them. Breath they had not, nor blood, nor senses, nor language possessed, nor life-hue. Odin gave them breath. Hoenir gave them senses (shape). Blood and life-hue was given by Lothur.

We are the forbears of the trees. One does not just carve runes, one recreates this ritual. By chanting the name of the the rune, one give the rune breath, the energy of its name. By carving it, one gives the rune senses (shape). By coloring the rune red, one gives it life's hue.

When one makes a set of runes they create life.

I will cut and mark and weather the wood it will be up to the one receiving these to give them breath and energy. And to color them in the style of life. -

-

Permalink Reply by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler on May 4, 2010 at 1:21am

-

three sized materials from 10.00 to 20.00 from about and inch to just at 1 1/2 inches. A couple of hours to cut and inscribe and seal at $10.00 an hour. and you will have them. All I need to know is small med or large sized.

-

-

Permalink Reply by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler on May 17, 2010 at 4:30pm

-

$45.00 +sh/I$13.45 for total of 58.45 round up to even $60.00 for taxes.

2010-05-17 16:32:21) PMM SITE = mynushka: thanks for this precise info !

(2010-05-17 16:33:03) Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler: it is as I can do

(2010-05-17 16:33:54) PMM SITE = mynushka: this was very important to me to know ... because I receive money each month on the 1th and 20th

(2010-05-17 16:34:08) Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler: 3 more days

(2010-05-17 16:34:46) PMM SITE = mynushka: ok so next ? you make it, than I pay it and than receive it ?

(2010-05-17 16:34:51) Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler: then I will have to run to the wood place and cut things and inscribe them and seal them then send them

(2010-05-17 16:35:22) Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler: weel I do like getting at least 1/2 up frount so can get the materials

(2010-05-17 16:35:43) PMM SITE = mynushka: ok

(2010-05-17 16:35:47) Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler: you may even want to look through the draw string bags to find one you like them to go into

(2010-05-17 16:36:54) PMM SITE = mynushka: so, to start things up I have to pay half the amount price like 30 us box... is that it ?

(2010-05-17 16:36:59) Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler: yes

(2010-05-17 16:37:19) PMM SITE = mynushka: ok -

-

Permalink Reply by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler on June 8, 2010 at 3:53pm

-

Wondering if this is still to be done or if not. Just have no seen words upon ant direction. So am asking of it at this time.

-

Events

-

2014 is the Chinese Year of the Horse

February 17, 2026 at 12am to February 5, 2027 at 12am – where & how you choose

Birthdays

Birthdays Tomorrow

Important (read & understand)

Skype: Travelingraggyman

Email and Instant Messenger:

TravelerinBDFSM @ aol/aim; hotmail; identi.ca; live & yahoo

OR

Travelingraggyman @ gmail and icq ***

1AWARD UPDATES & INFORMATION

10,000 votes - Platinum Award

5,000 votes - Gold Award

2,500 votes - Silver Award

1,000 votes - Bronze Award

300 votes - Pewter Award

100 votes - Copper Award

Member of the Associated Posting System {APS}

This allows members on various sites to share information between sites and by providing a by line with the original source it credits the author with the creation.

Legal Disclaimer

***************We here at Traveling within the World are not responsible for anything posted by individual members. While the actions of one member do not reflect the intentions of the entire social network or the Network Creator, we do ask that you use good judgment when posting. If something is considered to be inappropriate it will be removed

Site Meter

This site is strictly an artist operational fan publication, no copyright infringement intended

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries had its humble beginnings as an idea of a few artisans and craftsmen who enjoy performing with live steel fighting. As well as a patchwork quilt tent canvas. Most had prior military experience hence the name.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries.

Vendertainers that brought many things to a show and are know for helping out where ever they can.

As well as being a place where the older hand made items could be found made by them and enjoyed by all.

We expanded over the years to become well known at what we do. Now we represent over 100 artisans and craftsman that are well known in their venues and some just starting out. Some of their works have been premiered in TV, stage and movies on a regular basis.

Specializing in Medieval, Goth , Stage Film, BDFSM and Practitioner.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries a Dept of, Ask For IT was started by artists and former military veterans, and sword fighters, representing over 100 artisans, one who made his living traveling from fair to festival vending medieval wares. The majority of his customers are re-enactors, SCAdians and the like, looking to build their kit with period clothing, feast gear, adornments, etc.

Likewise, it is typical for these history-lovers to peruse the tent (aka mobile store front) and, upon finding something that pleases the eye, ask "Is this period?"

A deceitful query!! This is not a yes or no question. One must have a damn good understanding of European history (at least) from the fall of Rome to the mid-1600's to properly answer. Taking into account, also, the culture in which the querent is dressed is vitally important. You see, though it may be well within medieval period, it would be strange to see a Viking wearing a Caftan...or is it?

After a festival's time of answering weighty questions such as these, I'd sleep like a log! Only a mad man could possibly remember the place and time for each piece of kitchen ware, weaponry, cloth, and chain within a span of 1,000 years!! Surely there must be an easier way, a place where he could post all this knowledge...

Traveling Within The World is meant to be such a place. A place for all of these artists to keep in touch and directly interact with their fellow geeks and re-enactment hobbyists, their clientele.

© 2025 Created by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler.

Powered by

![]()