Traveling within the World

Linking your favorite traveling artists across the globe

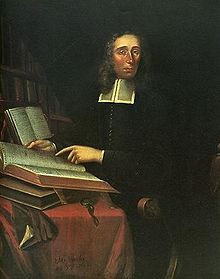

The Superior Court of Judicature, 1693

In January 1693, the new Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize and General Gaol Delivery convened in Salem, Essex County, again headed by William Stoughton, as Chief Justice, with Anthony Checkley continuing as the Attorney General, and Jonathan Elatson as Clerk of the Court. The first five cases tried in January 1693 were of the five people who had been indicted but not tried in September: Sarah Buckley, Margaret Jacobs, Rebecca Jacobs, Mary Whittredge, and Job Tookey. All were found not guilty. Grand juries were held for many of those remaining in jail. Charges were dismissed against many, but sixteen more people were indicted and tried, three of whom were found guilty: Elizabeth Johnson Jr., Sarah Wardwell, and Mary Post. When Stoughton wrote the warrants for the execution of these women and the others remaining from the previous court, Governor Phips pardoned them, sparing their lives. In late January/early February, the Court sat again in Charlestown, Middlesex County, and held grand juries and tried five people: Sarah Cole (of Lynn), Lydia Dustin & Sarah Dustin, Mary Taylor , and Mary Toothaker. All were found not guilty, but were not released until they paid their jail fees. Lydia Dustin died in jail on March 10, 1693. At the end of April, the Court convened in Boston, Suffolk County, and cleared Capt. John Alden by proclamation, and heard charges against a servant girl, Mary Watkins, for falsely accusing her mistress of witchcraft. In May, the Court convened in Ipswich, Essex County, held a variety of grand juries who dismissed charges against all but five people. Susannah Post, Eunice Frye, Mary Bridges Jr., Mary Barker, and William Barker Jr. were all found not guilty at trial, putting an end to the episode.

Legal procedures used

Overview

After someone concluded that a loss, illness or death had been caused by witchcraft, the accuser would enter a complaint against the alleged witch with the local magistrates,

If the complaint was deemed credible, the magistrates would have the person arrested and brought in for a public examination, essentially an interrogation, where the magistrates pressed the accused to confess.

If the magistrates at this local level were satisfied that the complaint was well-founded, the prisoner was handed over to be dealt with by a superior court. In 1692, the magistrates opted to wait for the arrival of the new charter and governor, who would establish a Court of Oyer and Terminer to handle these cases.

The next step, at the superior court level, was to summon witnesses before a grand jury.

A person could be indicted on charges of afflicting with witchcraft, or for making an unlawful covenant with the Devil. Once indicted, the defendant went to trial, sometimes on the same day, as in the case of the first person indicted and tried on June 2, Bridget Bishop, who was executed on June 10, 1692.

There were four execution dates, with one person executed on June 10, 1692,five executed on July 19, 1692 (Sarah Good, Rebecca Nurse, Susannah Martin, Elizabeth Howe & Sarah Wildes), another five executed on August 19, 1692 (Martha Carrier, John Willard, George Burroughs, George Jacobs, Sr., and John Proctor), and eight on September 22, 1692 (Mary Eastey, Martha Corey, Ann Pudeator, Samuel Wardwell, Mary Parker, Alice Parker, Wilmot Redd, and Margaret Scott). Several others, including Elizabeth (Bassett) Proctor and Abigail Faulkner, were convicted but given temporary reprieves because they were pregnant. Though convicted, they would not be hanged until they had given birth. Five other women were convicted in 1692, but sentence was never carried out: Ann Foster (who later died in prison), her daughter Mary Lacy Sr., Abigail Hobbs, Dorcas Hoar, and Mary Bradbury.

Giles Corey, an 80-year-old farmer from the southeast end of Salem (called Salem Farms), refused to enter a plea when he came to trial in September. The judges applied an archaic form of punishment called peine forte et dure, in which stones were piled on his chest until he could no longer breathe. After two days of peine fort et dure, Corey died without entering a plea. His refusal to plead has sometimes been explained as a way of preventing his estate from being confiscated by the Crown, but according to historian Chadwick Hansen, much of Corey's property had already been seized, and he had made a will in prison: "His death was a protest... against the methods of the court". This echoes the perspective of a contemporary critic of the trials, Robert Calef, who claimed, "Giles Corey pleaded not Guilty to his Indictment, but would not put himself upon Tryal by the Jury (they having cleared none upon Tryal) and knowing there would be the same Witnesses against him, rather chose to undergo what Death they would put him to."

Not even in death were the accused witches granted peace or respect. As convicted witches, Rebecca Nurse and Martha Corey had been excommunicated from their churches and none was given proper burial. As soon as the bodies of the accused were cut down from the trees, they were thrown into a shallow grave and the crowd would disperse. Oral history claims that the families of the dead reclaimed their bodies after dark and buried them in unmarked graves on family property. The record books of the time do not mention the deaths of any of those executed.

Spectral evidence

Much, but not all, of the evidence used against the accused was spectral evidence, or the testimony of the afflicted who claimed to see the apparition or the shape of the person who was allegedly afflicting them. The theological dispute that ensued about the use of this evidence centered on whether a person had to give permission to the Devil for his/her shape to be used to afflict. Opponents claimed that the Devil was able to use anyone's shape to afflict people, but the Court contended that the Devil could not use a person's shape without that person's permission; therefore, when the afflicted claimed to see the apparition of a specific person, that was accepted as evidence that the accused had been complicit with the Devil. Increase Mather and other ministers sent a letter to the Court, "The Return of Several Ministers Consulted," urging the magistrates not to convict on spectral evidence alone (spectral evidence was later ruled inadmissible, which caused a dramatic reduction in the rate of convictions and may have hastened the end of the trials). A copy of this letter was printed in Increase Mather's Cases of Conscience, published in 1693. The publication A Tryal of Witches, was used by the Magistrates at Salem, when looking for a precedent in allowing spectral evidence. Finding that no lesser person than the jurist Sir Matthew Hale had permitted this evidence, supported by the eminent philosopher, physician and author Thomas Browne, to be used in the Bury St Edmunds witch trial and the accusations against two Lowestoft women, held in 1662 in Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, England, they also accepted its validity and the trials proceeded. Other evidence included the confessions of the accused, the testimony of a person who confessed to being a witch identifying others as witches, the discovery of poppits, books of palmistry and horoscopes, or pots of ointments in the possession or home of the accused, and the existence of so-called witch's teats on the body of the accused. A witch's teat was said to be a mole or blemish somewhere on the body that was insensitive to touch; discovery of such insensitive areas was considered de facto evidence of witchcraft, though in practice, the witch's teat was usually insensitive by design, with examiners using secretly dulled needles to claim that the accused could not feel the prick of a pin.

The witch cake

At some point in February 1692, likely between the time when the afflictions began but before specific names were mentioned, a neighbor of Rev. Parris, Mary Sibly (aunt of the afflicted Mary Walcott), instructed John Indian, one of the minister's slaves, to make a witch cake, using traditional English white magic to discover the identity of the witch who was afflicting the girls. The cake, made from rye meal and urine from the afflicted girls, was fed to a dog.

According to English folk understanding of how witches accomplished affliction, when the dog ate the cake, the witch herself would be hurt because invisible particles she had sent to afflict the girls remained in the girls' urine, and her cries of pain when the dog ate the cake would identify her as the witch. This superstition was based on the Cartesian "Doctrine of Effluvia", which posited that witches afflicted by the use of "venomous and malignant particles, that were ejected from the eye", according to the October 8, 1692 letter of Thomas Brattle, a contemporary critic of the trials.

According to the Records of the Salem-Village Church, Parris spoke with Sibly privately on March 25, 1692 about her "grand error" and accepted her "sorrowful confession." That Sunday, March 27, during his Sunday sermon, he addressed his congregation about the "calamities" that had begun in his own household, but stated, "it never brake forth to any considerable light, until diabolical means were used, by the making of a cake by my Indian man, who had his direction from this our sister, Mary Sibly," going on to admonish all against the use of any kind of magic, even white magic, because it was essentially, "going to the Devil for help against the Devil." Mary Sibley publicly acknowledged the error of her actions before the congregation, who voted by a show of hands that they were satisfied with her admission of error.

Other instances appear in the records of the episode that demonstrated a continued belief by members of the community in this effluvia as legitimate evidence, including accounts in two statements against Elizabeth Howe that people had suggested cutting off and burning an ear of two different animals Howe was thought to have afflicted, to prove she was the one who had bewitched them to death.

Traditionally, the allegedly afflicted girls are said to have been entertained by Parris' slave woman, Tituba, who supposedly taught them about voodoo in the kitchen of the parsonage during the winter of 1692, although there is no contemporary evidence to support the story. A variety of secondary sources, starting with Charles W. Upham in the 19th century, typically relate that a circle of the girls, with Tituba's help, tried their hands at fortune telling using the white of an egg and a mirror to create a primitive crystal ball to divine the professions of their future spouses and scared one another when one supposedly saw the shape of a coffin instead. The story is drawn from John Hale's book about the trials, but in his account, only one of the girls, not a group of them, had confessed to him afterwards that she had once tried this. Hale did not mention Tituba as having any part of it, nor when it had occurred. Yet the record of her trial with Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne holds her giving an energetic confession, speaking before the court of "creatures who inhabit the invisible world," and "the dark rituals which bind them together in service of Satan," and implicating both Good and Osborne while asserting that "many other people in the colony were engaged in the devil's conspiracy against the Bay."

Tituba's race is often cited as Carib-Indian or of African descent, but contemporary sources describe her only as an "Indian." Research by Elaine Breslaw has suggested that she may well have been captured in what is now Venezuela and brought to Barbados, and so may have been an Arawak Indian. Other slightly later descriptions of her, by Gov. Thomas Hutchinson writing his history of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 18th century, describe her as a "Spanish Indian."[39] In that day, that typically meant a Native American from the Carolinas/Georgia/Florida. Contrary to the folklore, there is no evidence to support the assertion that Tituba told any of the girls any stories about using magic.

The touch test

The most infamous employment of the belief in effluvia – and in direct opposition to what Parris had advised his own parishioners in Salem Village – was the touch test used in Andover during preliminary examinations in September 1692. As several of those accused later recounted, "we were blindfolded, and our hands were laid upon the afflicted persons, they being in their fits and falling into their fits at our coming into their presence, as they said. Some led us and laid our hands upon them, and then they said they were well and that we were guilty of afflicting them; whereupon we were all seized, as prisoners, by a warrant from the justice of the peace and forthwith carried to Salem" Rev. John Hale explained how this supposedly worked: "the Witch by the cast of her eye sends forth a Malefick Venome into the Bewitched to cast him into a fit, and therefore the touch of the hand doth by sympathy cause that venome to return into the Body of the Witch again".

Contemporary commentary on the trials

Various accounts and opinions about the proceedings began to appear in print in 1692.

Deodat Lawson, a former minister in Salem Village, visited Salem Village in March and April, 1692, and published an account in Boston in 1692 of what he witnessed and heard, called "A Brief and True Narrative of Some Remarkable Passages Relating to Sundry Persons Afflicted by Witchcraft, at Salem Village: Which happened from the Nineteenth of March, to the Fifth of April, 1692".

Rev. William Milbourne, a Baptist minister in Boston, publicly petitioned the General Assembly in early June, 1692, challenging the use of spectral evidence by the Court. Milbourne had to post £200 bond or be arrested for "contriving, writing and publishing the said scandalous Papers".

On June 15, 1692, twelve local ministers—including Increase Mather, Samuel Willard, Cotton Mather—submitted The Return of several Ministers to the Governor and Council in Boston, cautioning the authorities not to rely entirely on the use of spectral evidence, stating, "Presumptions whereupon persons may be Committed, and much more, Convictions whereupon persons may be Condemned as Guilty of Witchcrafts, ought certainly to be more considerable, than barely the Accused Persons being Represented by a Spectre unto the Afflicted".

Sometime in 1692, minister of the First Church in Boston, Samuel Willard anonymously published a short tract in Philadelphia entitled, "Some Miscellany Observations On our present Debates respecting Witchcrafts, in a Dialogue Between S. & B." The authors were listed as "P.E. and J. A." (Philip English and John Alden), but is generally attributed to Willard. In it, two characters, S (Salem) and B (Boston), discuss the way the proceedings were being conducted, with "B" urging caution about the use of testimony from the afflicted and the confessors, stating, "whatever comes from them is to be suspected; and it is dangerous using or crediting them too far".

Sometime in September 1692, at the request of Governor Phips, Cotton Mather wrote "Wonders of the Invisible World: Being an Account of the Tryals of Several Witches, Lately Executed in New-England," as a defense of the trials, to "help very much flatten that fury which we now so much turn upon one another". It was published in Boston and London in 1692, although dated 1693, with an introductory letter of endorsement by William Stoughton, the Chief Magistrate. The book included accounts of five trials, with much of the material copied directly from the court records supplied to Mather by Stephen Sewall, his friend and Clerk of the Court.

Cotton Mather's father, Increase Mather, published "Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits," dated October 3, 1692, after the last trials by the Court of Oyer & Terminer, although the title page lists the year of publication as "1693." In it, Mather repeated his caution about the reliance on spectral evidence, stating "It were better that Ten Suspected Witches should escape, than that one Innocent Person should be Condemned". Second and third editions of this book were published in Boston and London in 1693, the third of which also included Lawson's Narrative and the anonymous "A Further Account of the Tryals of the New-England Witches, sent in a Letter from thence, to a Gentleman in London."

A wealthy businessman in Boston and fellow Harvard graduate, Thomas Brattle circulated a letter in manuscript form in October 1692, in which he criticized the methods used by the Court to determine guilt, including the use of the touch test and the testimony of confessors, stating, "they are deluded, imposed upon, and under the influence of some evill spirit; and therefore unfit to be evidences either against themselves, or any one else"

Aftermath and closure

Although the last trial was held in May 1693, public response to the events has continued. In the decades following the trials, the issues primarily had to do with establishing the innocence of the individuals who were convicted and compensating the survivors and families, and in the following centuries, the descendants of those unjustly accused and condemned have sought to honor their memories.

Tags:

Replies to This Discussion

Events

-

2014 is the Chinese Year of the Horse

February 17, 2026 at 12am to February 5, 2027 at 12am – where & how you choose

Birthdays

Birthdays Today

Birthdays Tomorrow

Important (read & understand)

Skype: Travelingraggyman

Email and Instant Messenger:

TravelerinBDFSM @ aol/aim; hotmail; identi.ca; live & yahoo

OR

Travelingraggyman @ gmail and icq ***

1AWARD UPDATES & INFORMATION

10,000 votes - Platinum Award

5,000 votes - Gold Award

2,500 votes - Silver Award

1,000 votes - Bronze Award

300 votes - Pewter Award

100 votes - Copper Award

Member of the Associated Posting System {APS}

This allows members on various sites to share information between sites and by providing a by line with the original source it credits the author with the creation.

Legal Disclaimer

***************We here at Traveling within the World are not responsible for anything posted by individual members. While the actions of one member do not reflect the intentions of the entire social network or the Network Creator, we do ask that you use good judgment when posting. If something is considered to be inappropriate it will be removed

Site Meter

This site is strictly an artist operational fan publication, no copyright infringement intended

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries had its humble beginnings as an idea of a few artisans and craftsmen who enjoy performing with live steel fighting. As well as a patchwork quilt tent canvas. Most had prior military experience hence the name.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries.

Vendertainers that brought many things to a show and are know for helping out where ever they can.

As well as being a place where the older hand made items could be found made by them and enjoyed by all.

We expanded over the years to become well known at what we do. Now we represent over 100 artisans and craftsman that are well known in their venues and some just starting out. Some of their works have been premiered in TV, stage and movies on a regular basis.

Specializing in Medieval, Goth , Stage Film, BDFSM and Practitioner.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries a Dept of, Ask For IT was started by artists and former military veterans, and sword fighters, representing over 100 artisans, one who made his living traveling from fair to festival vending medieval wares. The majority of his customers are re-enactors, SCAdians and the like, looking to build their kit with period clothing, feast gear, adornments, etc.

Likewise, it is typical for these history-lovers to peruse the tent (aka mobile store front) and, upon finding something that pleases the eye, ask "Is this period?"

A deceitful query!! This is not a yes or no question. One must have a damn good understanding of European history (at least) from the fall of Rome to the mid-1600's to properly answer. Taking into account, also, the culture in which the querent is dressed is vitally important. You see, though it may be well within medieval period, it would be strange to see a Viking wearing a Caftan...or is it?

After a festival's time of answering weighty questions such as these, I'd sleep like a log! Only a mad man could possibly remember the place and time for each piece of kitchen ware, weaponry, cloth, and chain within a span of 1,000 years!! Surely there must be an easier way, a place where he could post all this knowledge...

Traveling Within The World is meant to be such a place. A place for all of these artists to keep in touch and directly interact with their fellow geeks and re-enactment hobbyists, their clientele.

© 2024 Created by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler.

Powered by

![]()