Traveling within the World

Linking your favorite traveling artists across the globe

Cannon Tools & Implements General knowledge

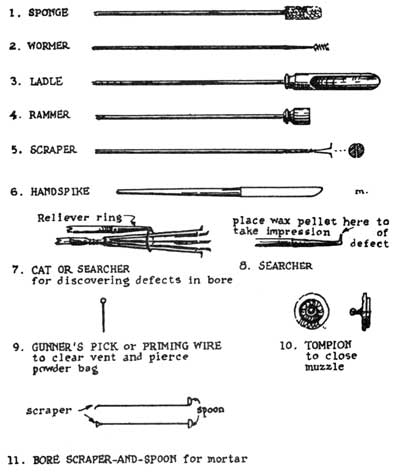

Gunner's equipment was numerous. There were the tompion (a lid that fitted over the muzzle of the gun to keep wind and weather out of the bore) and the lead cover for the vent; water buckets for the sponges and passing boxes for the powder; scrapers and tools for "searching" the bore to find dangerous cracks or holes; chocks for the wheels; blocks and rollers, lifting jacks, and gins for moving guns; and drills and augers for clearing the vent (figs. 17, 44). But among the most important tools for every day firing were the following:

FIGURE 44—EIGHTEENTH CENTURY GUNNER'S EQUIPMENT. (Not to scale.)

The sponge was a wooden cylinder about a foot long, the same diameter as the shot, and covered with lambskin. Like all bore tools, it was mounted on a long staff; after being dampened with water, it was used for cleaning the bore of the piece after firing. Essentially, sponging made sure there were no sparks in the bore when the new charge was put in. Often the sponge was on the opposite end of the rammer, and sometimes, instead of being lambskin-covered, the sponge was a bristle brush.

The wormer was a double screw, something like a pair of intertwined corkscrews, fixed to a long handle. Inserted in the gun bore and twisted, it seized and drew out wads or the remains of cartridge bags stuck in the gun after firing. Worm screws were sometimes mounted in the head of the sponge, so that the piece could be sponged and wormed at the same time.

The ladle was the most important of all the gunner's tools in the early years, since it was not only the measure for the powder but the only way to dump the powder in the bore at the proper place. It was generally made of copper, the same gauge as the windage of the gun; that is, the copper was just thick enough to fit between ball and bore.

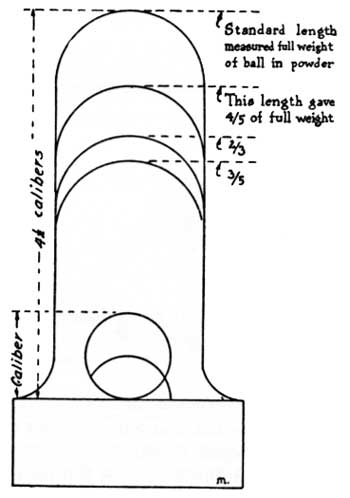

Essentially, the ladle is merely a scoop, a metal cylinder secured to a wooden disk on a long staff. But before the introduction of the powder cartridge, cutting a ladle to the right size was one of the most important accomplishments a gunner had to learn. Collado, that Spanish mathematician of the sixteenth century, used the culverin ladle as the master pattern (fig. 45). It was 4-1/2 calibers long and would carry exactly the weight of the ball in powder. Ladles for lesser guns could be proportioned (that is, shortened) from the master pattern.

The ladle full of powder was pushed home in the bore. Turning the handle dumped the charge, which then had to be packed with the rammer. As powder charges were lessened in later years, the ladle was shortened; by 1750, it was only three shot diameters long. With cartridges, the ladle was no longer needed for loading the gun, but it was still handy for withdrawing the round.

FIGURE 45—SIXTEENTH CENTURY PATTERN FOR GUNNER'S LADLE.

The rammer was a wooden cylinder about the same diameter and length as the shot. It pushed home the powder charge, the wad, and the shot. As a precaution against faulty or double loading, marks on the rammer handle showed the loaders when the different parts of the charge were properly seated.

The gunner's pick or priming wire was a sharp pointed tool resembling a common ice pick blade. It was used to clear the vent of the gun and to pierce the powder bag so that flame from the primer could ignite the charge.

Handspikes were big pinch bars to manhandle cannon. They were used to move the carriage and to lift the breech of the gun so that the elevating quoin or screw might be adjusted. They were of different types (figs. 33a, 44), but were essentially 6-foot-long wooden poles, shod with iron. Some of them, like the Marsilly handspike (fig. 11), had rollers at the toe so that the wheelless rear of the carriage could be lifted with the handspike and rolled with comparative ease.

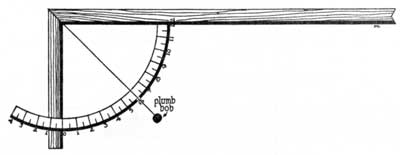

The gunner's quadrant (fig. 46), invented by Tartaglia about 1545, was an aiming device so basic that its principle is still in use today. The instrument looked like a carpenter's square, with a quarter-circle connecting the two arms. From the angle of the square dangled a plumb bob. The gunner laid the long arm of the quadrant in the bore of the gun, and the line of the bob against the graduated quarter-circle showed the gun's angle of elevation.

The addition of the quadrant to the art of artillery opened a whole new field for the mathematicians, who set about compiling long, complicated and jealously guarded tables for the gunner's guidance. But the theory was simple: since a cannon at 45° elevation would fire ten times farther than it would when the barrel was level (at zero° elevation), the quadrant should be marked into ten equal parts; the range of the gun would therefore increase by one-tenth each time the gun was elevated to the next mark on the quadrant. In other words, the gunner could get the range he wanted simply by raising his piece to the proper mark on the instrument.

FIGURE 46—SEVENTEENTH CENTURY GUNNER'S QUADRANT. The long end of the quadrant was laid in the bore of the cannon. The plumb bob indicated the degree of elevation on the scale.

Collado explained how it worked in the 1590's. "We experimented with a culverin that fired a 20-pound iron ball. At point-blank the first shot ranged 200 paces. At 45-degree elevation it shot ten times farther, or 2,000 paces. . . . If the point-blank range is 200 paces, then elevating to the first position, or a tenth part of the quadrant, will gain 180 paces more, and advancing another point will gain so much again. It is the same with the other points up to the elevation of 45 degrees; each one gains the same 180 paces." Collado admitted that results were not always consistent with theory, but it was many years before the physicists understood the effect of air resistance on the trajectory of the projectile.

Sights on cannon were usually conspicuous by their absence in the early days. A dispart sight (an instrument similar to the modern infantry rifle sight), which compensated for the difference in diameter between the breech and the muzzle, was used in 1610, but the average artilleryman still aimed by sighting over the barrel. The Spanish gunner, however, performed an operation that put the bore parallel to the gunner's line of sight, and called it "killing the vivo" (matar el vivo). How vivo affected aiming is easily seen: with its bore level, a 4-pounder falconet ranged 250 paces. But when the top of the gun was level, the bore was slightly elevated and the range almost doubled to 440 paces.

To "kill the vivo," you first had to find it. The gunner stuck his pick into the vent down to the bottom of the bore and marked the pick to show the depth. Next he took the pick to the muzzle, stood it up in the bore, and marked the height of the muzzle. The difference between the two marks, with an adjustment for the base ring (which was higher than the vent), was the vivo. A little wedge of the proper size, placed under the breech, would then eliminate the troublesome vivo.

During the first half of the 1700's Spanish cannon of the "new invention" were made with a notch at the top of the base ring and a sighting button on the muzzle, and these features were also adopted by the French. But they soon went out of use. There was some argument, as late as the 1750's, about the desirability of casting the muzzle the same size as the base ring, so that the sighting line over the gun would always be parallel to the bore; but, since the gun usually had to be aimed higher than the objective, gunners claimed that a fat muzzle hid their target!

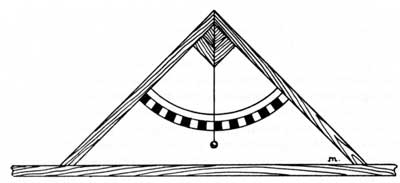

FIGURE 47—SEVENTEENTH CENTURY GUNNER'S LEVEL. This tool was useful in many ways, but principally for finding the line of sight on the barrel of the gun.

Common practice for sighting, as late as the 1850's, was to find the center line at the top of the piece, mark it with chalk or filed notches, and use it as a sighting line. To find this center line, the gunner laid his level (fig. 47) first on the base ring, then on the muzzle. When the instrument was level atop these rings, the plumb bob was theoretically over the center line of the cannon. But guns were crudely made, and such a line on the outside of the piece was not likely to coincide exactly with the center line of the bore, so there was still ample opportunity for the gunner to exercise his "art." Nonetheless the marked lines did help, for the gunner learned by experiment how to compensate for errors.

Fixed rear sights came into use early in the 1800's, and tangent sights (graduated rear sights) were in use during the Civil War. The trunnion sight, a graduated sight attached to the trunnion, could be used when the muzzle had to be elevated so high that it blocked the gunner's view of the target.

Naval gunnery officers would occasionally order all their guns trained at the same angle and elevated to the same degree. The gunner might not even see his target. While with the crude traversing mechanism of the early 1800's the gunners may not have laid their pieces too accurately, at least it was a step toward the indirect firing technique of later years which was to take full advantage of the longer ranges possible with modern cannon. Use of tangent and trunnion sights brought gunnery further into the realm of mathematical science; the telescopic sight came about the middle of the nineteenth century; gunners were developing into technicians whose job was merely to load the piece and set the instruments as instructed by officers in fire control posts some distance away from the gun.

Tags:

Replies to This Discussion

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on February 20, 2011 at 1:24pm

-

The Practice of Gunnery

The oldtime gunner was not only an artist, vastly superior to the average soldier, but, when circumstances permitted, he performed his wizardry with all due ceremony. Diego Ufano, Governor of Antwerp, watched a gun crew at work about 1500:

"The piece having arrived at the battery and being provided with all needful materials, the gunner and his assistants take their places, and the drummer is to beat a roll. The gunner cleans the piece carefully with a dry rammer, and in pulling out the said rammer gives a dab or two to the mouth of the piece to remove any dirt adhering." (At this point it was customary to make the sign of the cross and invoke the intercession of St. Barbara.)

"Then he has his assistant hold the sack, valise, or box of powder, and filling the charger level full, gives a slight movement with the other hand to remove any surplus, and then puts it into the gun as far as it will go. Which being done, he turns the charger so that the powder fills the breech and does not trail out on the ground, for when it takes fire there it is very annoying to the gunner." (And probably to the gentleman holding the sack.)

"After this he will take the rammer, and, putting it into the gun, gives two or three good punches to ram the powder well in to the chamber, while his assistant holds a finger in the vent so that the powder does not leap forth. This done, he takes a second charge of powder and deposits it like the first; then puts in a wad of straw or rags which will be well packed to gather up all the loose powder. This having been well seated with strong blows of the rammer, he sponges out the piece.

"Then the ball, well cleaned by his assistant, since there is danger to the gunner in balls to which sand or dirt adhere, is placed in the piece without forcing it till it touches gently on the wad, the gunner being careful not to hold himself in front of the gun, for it is silly to run danger without reason. Finally he will put in one more wad, and at another roll of drums the piece is ready to fire."

Maximum firing rate for field pieces in the early days was eight rounds an hour. It increased later to 100 rounds a day for light guns and 30 for heavy pieces. (Modern nonautomatic guns can fire 15 rounds per minute.) After about 40 rounds the gun became so hot it was unsafe to load, where upon it was "refreshed"' with an hour's rest.

Approved aiming procedure was to make the first shot surely short, in order to have a measurement of the error. The second shot would be at greater elevation, but also cautiously short. After the third round, the gunner could hope to get hits. Beginners were cautioned against the desire to hit the target at the first shot, for, said a celebrated artillerist, ". . . you will get overs and cannot estimate how much over."

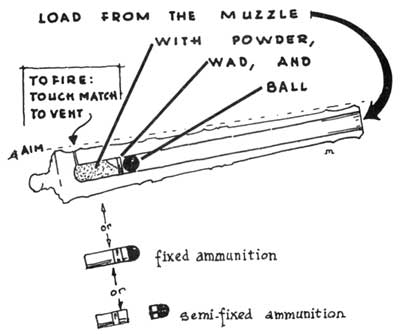

FIGURE 48—LOADING A CANNON. Muzzle-loading smoothbore cannon were used for almost 700 years.As gunners gradually became professional soldiers, gun drills took on a more military aspect, as these seventeenth century commands show:

1. Put back your piece.

2. Order your piece to load.

3. Search your piece.

4. Sponge your piece.

5. Fill your ladle.

6. Put in your powder.

7. Empty your ladle.8. Put up your powder.

9. Thrust home your wad.

10. Regard your shot.

11. Put home your shot gently.

12. Thrust home your wad with three strokes.

13. Gauge your piece.Gunners had no trouble finding work, as is singularly illustrated by the case of Andrew Ransom, a stray Englishman captured near St. Augustine in the late 1600's. He was condemned to death. The executional device failed, however, and the padres in attendance took it as an act of God and led Ransom to sanctuary at the friary. Meanwhile, the Spanish governor learned this man was an artillerist and a maker of "artificial fires." The governor offered to "protect" him if he would live at the Castillo and put his talents to use. Ransom did.

By 1800, although guns could be served with as few as three men, efficient drill usually called for a much larger force. The smallest crew listed in the United States Navy manual of 1866 was seven: first and second gun captains, two loaders, two spongers, and a "powder monkey" (powder boy). An 11-inch pivot-gun on its revolving carriage was served by 24 crewmen and a powderman. In the field, transportation for a 24-pounder siege gun took 10 horses and 5 drivers.

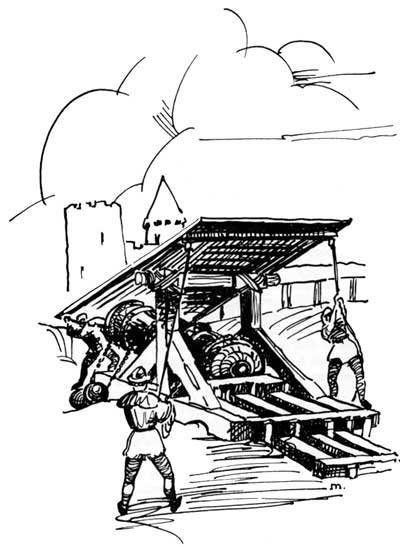

FIGURE 49—A SIEGE BOMBARD OF THE 1500's.Twelve rounds an hour was good practice for heavy guns during the Civil War period, although the figure could be upped to 20 rounds. By this date, of course, although the principles of muzzle loading had not changed, actual loading of the gun was greatly simplified by using fixed and semi-fixed ammunition. Loading technique varied with the gun, but the following summary of drill from the United States Heavy Ordnance Manual of 1861 gives a fair idea of how the crew handled a siege gun:

In the first place, consider that the equipment is all in its proper place. The gun is on a two-wheeled siege carriage, and is "in battery," or pushed forward on the platform until the muzzle is in the earthwork embrasure. On each side of the gun are three handspikes, leaning against the parapet. On the right of the gun a sponge and a rammer are laid on a prop, about 6 feet away from the carriage. Near the left muzzle of the gun is a stack of cannonballs, wads, and a "passbox" or powder bucket. Hanging from the cascabel are two pouches: the tube-pouch containing friction "tubes" (primers for the vent) and the lanyard; and the gunner's-pouch with the gunner's level, breech-sight, pick, gimlet, vent-punch, chalk, and fingerstall (a leather cover for the gunner's second left finger when the gun gets hot). Under the wheels are two chocks; the vent-cover is on the vent, a tompion in the muzzle; a broom leans against the parapet beyond the stack of cannonballs. A wormer, ladle, and wrench were also part of the battery equipment.

The crew consisted of a gunner and six cannoneers. At the command Take implements the gunner stepped to the cascabel and handed the vent-cover to No. 2; the tube-pouch he gave to No. 3; he put on his fingerstall, leveled the gun with the elevating screw, applied his level to base ring and muzzle to find the highest points of the barrel, and marked these points with chalk for a line of sight. His six crewmen took their positions about a yard apart, three men on each side of the gun, with handspikes ready.

From battery was the first command of the drill. The gunner stepped from behind the gun, while the handspikemen embarred their spikes. Cannoneers Nos. 1, 3, and 5 were on the right side of the gun, and the even-numbered men were on the left. Nos. 1 and 2 put their spikes under the front of the wheels; Nos. 3 and 4 embarred under the carriage cheeks to bear down on the rear spokes of the wheel; Nos. 5 and 6 had their spikes under the maneuvering bolts of the trail for guiding the piece away from the parapet. With the gunner's word Heave, the men at the wheels put on the pressure, and with successive heaves the gun was moved backward until the muzzle was clear of the embrasure by a yard. The crew then unbarred, and Nos. 1 and 2 chocked the wheels.

Load was the second command. Nos. 1, 2, and 4 laid down their spikes; No. 2 took out the tompion; No. 1 took up the sponge and put its wooly head into the muzzle; No. 2 stepped up to the muzzle and seized the sponge staff to help No. 1. In five counts they pushed the sponge to the bottom of the bore. Meanwhile, No. 4 took the passbox and went to the magazine for a cartridge.

FIGURE 50—GUN DRILL IN THE 1850's.The gunner put his finger over the vent, and with his right hand turned the elevating screw to adjust the piece conveniently for loading. No. 3 picked up the rammer.

At the command Sponge, the men at the sponge pressed the tool against the bottom of the bore and gave it three turns from right to left, then three turns from left to right. Next the sponge was drawn, and while No. 1 exchanged it for No. 3's rammer, the No. 2 man took the cartridge from No. 4, and put it in the bore. He helped No. 1 push it home with the rammer, while No. 4 went for a ball and, if necessary, a wad.

Ram! The men on the rammer drew it out an arm's length and rammed the cartridge with a single stroke. No. 2 took the ball from No. 4, while No. 1 threw out the rammer. With the ball in the bore, both men again manned the rammer to force the shot home and delivered a final single-stroke ram. No. 1 put the rammer back on its prop. The gunner stuck his pick into the vent to prick open the powder bag.

The command In battery was the signal for the cannoneers to man the handspikes again, Nos. 1, 2, 3, and 4 working at the wheels and Nos. 5 and 6 guiding the trail as before. After successive heaves, the gunner halted the piece with the wheels touching the hurter—the timber laid at the foot of the parapet to stop the wheels.

Point was the next order. No. 3, the man with the tube-pouch, got out his lanyard and hooked it to a primer. Nos. 5 and 6 put their handspikes under the trail, ready to move the gun right or left. The gunner went to the breech of the gun, removed his pick from the vent, and, sighting down the barrel, directed the spikemen: he would tap the right side of the breech, and No. 5 would heave on his handspike to inch the trail toward the left. A tap on the left side would move No. 6 in the opposite direction. Next, the gunner put the breech-sight (if he needed it) carefully on the chalk line of the base ring and ran the elevating screw to the proper elevation.

As soon as the gun was properly laid, the gunner said Ready and signaled with both hands. He took the breech-sight off the gun and walked over to windward, where he could watch the effect of the shot. Nos. 1 and 2 had the chocks, ready to block the wheels at the end of the recoil. No. 3 put the primer in the vent, uncoiled the lanyard and broke a full pace to the rear with his left foot. He stretched the lanyard, holding it in his right hand.

At Fire! No. 3 gave a smart pull on the lanyard. The gun fired, the carriage recoiled, and Nos. 1 and 2 chocked the wheels. No. 3 rewound his lanyard, and the gunner, having watched the shot, returned to his post.

The development of heavy ordnance through the ages is a subject with many fascinating ramifications, but this survey has of necessity been brief. It has only been possible to indicate the general pattern. Most of the interesting details must await the publication of much larger volumes. It is hoped, however, that enough information has been included herein to enhance the enjoyment that comes from inspecting the great variety of cannon and projectiles that are to be seen throughout the National Park System.

-

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on February 20, 2011 at 1:25pm

-

Glossary of Cannon

Terminology

Most technical phrases are explained in the text and illustrations (see fig. 51). For convenient reference, however, some important words are defined below:

Ballistics—the science dealing with the motion of projectiles.

Barbette carriage—as used here, a traverse carriage on which a gun is mounted to fire over a parapet.

Bomb, bombshell—see projectiles.

Breechblock—a movable piece which closes the breech of a cannon.

Caliber—diameter of the bore; also used to express bore length. A 30-caliber gun has a bore length 30 times the diameter of the bore.

Cartridge—a bag or case holding a complete powder charge for the cannon, and in some instances also containing the projectile.

Casemate carriage—as used here, a traverse carriage in a fort gunroom (casemate). The gun fired through an embrasure or loophole in the scarp of the room.

Chamber—the part of the bore which holds the propelling charge, especially when of different diameter than the rest of the bore; in chambered muzzle-loaders, the chamber diameter was smaller than that of the bore.

Elevation—the angle between the axis of a piece and the horizontal plane.

Fuze—a device to ignite the charge of a shell or other projectile.

Grommet—a rope ring used as a wad to hold a cannonball in place in the bore.

Gun—any firearm; in the limited sense, a long cannon with high muzzle velocity and flat trajectory.

Howitzer—a short cannon, intermediate between the gun and mortar.

Lay—to aim a gun.

Limber—a two-wheeled vehicle to which the gun trail is attached for transport.

Mandrel—a metal bar, used as a core around which metal may be forged or otherwise shaped.

Mortar—a very short cannon used for high or curved trajectory firing.

Point-blank—as used here, the point where the projectile, when fired from a level bore, first strikes the horizontal ground in front of the cannon.

Projectiles—canister or case shot: a can filled with small missiles that scatter after firing from the gun. Grape shot: a cluster of small iron balls, which scatter upon firing. Shell: explosive missile; a hollow cast-iron ball, filled with gunpowder, with a fuze to produce detonation; a long, hollow projectile, filled with explosive and fitted with a fuze. Shot: a solid projectile, non-explosive.

Quoin—a wedge placed under the breech of a gun to fix its elevation.

Range—The horizontal distance from a gun to its target or to the point where the projectile first strikes the ground. Effective range is the distance at which effective results may be expected, and is usually not the same as maximum range, which means the extreme limit of range.

Rotating band—a band of soft metal, such as copper, which encircles the projectile near its base. By engaging the lands of the spiral rifling in the bore, the band causes rotation of the projectile. Rotating bands for muzzle-loading cannon were expansion rings, and the powder blast expanded the ring into the rifling grooves.

Train—to aim a gun.

Trajectory—curved path taken by a projectile in its flight through the air.

Transom—horizontal beam between the cheeks of a gun carriage.

Traverse carriage—as used here, a stationary gun mount, consisting of a gun carriage on a wheeled platform which can be moved about a pivot for aiming the gun to right or left.

Windage—as used here, the difference between the diameter of the shot and the diameter of the bore.

parts of a cannon

FIGURE 51—THE PARTS OF A CANNON

Selected Bibliography for Cannon Information:

The following is a listing of the more important sources dealing with the development of artillery which have been consulted in the production of this booklet. None of the German or Italian sources have been included, since practically no German or Italian guns were used in this country.

SPANISH ORDNANCE. Luis Collado, "Platica Manual de la Altillería" ms., Milan 1592, and Diego Ufano, Artillerie, n. p., 1621, have detailed information on sixteenth century guns, and Tomás de Morla, Láminas pertenecientes al Tratado de Artillería, Madrid, 1803, illustrates eighteenth century material. Thor Borresen, "Spanish Guns and Carriages, 1686-1800" ms., Yorktown, 1938, summarizes eighteenth century changes in Spanish and French artillery. Information on colonial use of cannon can be found in mss. of the Archivo General de Indias as follows: Inventories of Castillo de San Marcos armament in 1683 (58-2-2,32/2), 1706 (58-1-27,89/2), 1740 (58-1-32), 1763 (86-7-11,19), Zuñiga's report on the 1702 siege of St. Augustine (58-2-8,B3) and Arredondo's "Plan de la Ciudad de Sn. Agustín de la Florida" (87-1-1/2, ms. map); and other works, including [Andres Gonzales de Barcía,] Ensayo Cronológico para la Historia General de la Florida, Madrid, 1723; J. T. Connor, editor, Colonial Records of Spanish Florida, Deland, 1930, Vol. II., Manuel de Montiano, Letters of Montiano (Collections of the Georgia Historical Society, v. VII, Pt. I), Savannah 1909; Albert Manucy, "Ordnance used at Castillo de San Marcos, 1672-1834," St. Augustine, 1939.

BRITISH ORDNANCE. For detailed information John Müller, Treatise of Artillery, London, 1756, has been the basic source for eighteenth century material. William Bourne, The Arte of Shooting in Great Ordnance, London, 1587, discusses sixteenth century artillery; and the anonymous New Method of Fortification, London, 1748, contains much seventeenth century information. For colonial artillery data there is John Smith, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-Englande, and the Summer Isles, Richmond, 1819; [Edward Kimber] Late Expedition to the Gates of St. Augustine, Boston, 1935; and C. L. Mowat, East Florida as a British Province, 1763-1784, Los Angeles, 1939. Charles J. Ffoulkes, The Gun-Founders of England, Cambridge, 1937, discusses the construction of early cannon in England.

FRENCH ORDNANCE. M. Surirey de Saint-Remy, Memories d'Artillerie, 3rd edition Paris, 1745, is the standard source for French artillery material in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Col. Favé, Ètudes sur le Passé et l'Avenir de L'Artillerie, Paris, 1863, is a good general history. Louis Figurier, Armes de Guerre, Paris, 1870, is also useful.

UNITED STATES ORDNANCE. Of first importance is Louis de Tousard, American Artillerist's Companion, 2 vols., Philadelphia, 1809-13. For performance and use of artillery during the 1860's the following sources are useful: John Gibbon, The Artillerist's Manual, New York, 1863; Q. A. Gillmore, Engineer and Artillery Operations against the Defences of Charleston Harbor in 1863, New York, 1865; his Official Report . . . of the Siege and Reduction of Fort Pulaski, Georgia, New York, 1862; and the Official Records of Union and Confederate Armies and Navies. Ordnance manuals of the period include: Instruction for Heavy Artillery, U. S., Charleston, 1861; Ordnance Instructions for the United States Navy, Washington, 1866; J. Gorgas, The Ordnance Manual for the Use of the Officers of the Confederate States Army, Richmond, 1863. For United States developments after 1860: L. L. Bruff, A Text-book of Ordnance and Gunnery, New York, 1903; F. T. Hines and F. W. Ward, The Service of Coast Artillery, New York, 1910; the U. S. Field Artillery School's Construction of Field Artillery Materiel and General Characteristics of Field Artillery Ammunition, Fort Sill, 1941.

GENERAL. For the history of artillery, as well as additional biographical and technical details, there is the Field Artillery School's excellent booklet, History of the Development of Field Artillery Materiel, Fort Sill, 1941. Henry W. L. Hime, The Origin of Artillery, New York, 1915, is most useful, as is that standard work, the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1894 edition: Arms and Armour, Artillery, Gunmaking, Gunnery, Gunpowder; 1938 edition: Artillery, Coehoorn, Engines of War, Fireworks, Gribeauval, Gun, Gunnery, Gunpowder, Musket, Ordnance, Rocket, Smallarms, and Tartagila. -

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on February 20, 2011 at 1:28pm

-

Selected Bibliography of

Cannon Information Sources

The following is a listing of the more important sources dealing with the development of artillery which have been consulted in the production of this booklet. None of the German or Italian sources have been included, since practically no German or Italian guns were used in this country (USA).

SPANISH ORDNANCE. Luis Collado, "Platica Manual de la Altillería" ms., Milan 1592, and Diego Ufano, Artillerie, n. p., 1621, have detailed information on sixteenth century guns, and Tomás de Morla, Láminas pertenecientes al Tratado de Artillería, Madrid, 1803, illustrates eighteenth century material. Thor Borresen, "Spanish Guns and Carriages, 1686-1800" ms., Yorktown, 1938, summarizes eighteenth century changes in Spanish and French artillery. Information on colonial use of cannon can be found in mss. of the Archivo General de Indias as follows: Inventories of Castillo de San Marcos armament in 1683 (58-2-2,32/2), 1706 (58-1-27,89/2), 1740 (58-1-32), 1763 (86-7-11,19), Zuñiga's report on the 1702 siege of St. Augustine (58-2-8,B3) and Arredondo's "Plan de la Ciudad de Sn. Agustín de la Florida" (87-1-1/2, ms. map); and other works, including [Andres Gonzales de Barcía,] Ensayo Cronológico para la Historia General de la Florida, Madrid, 1723; J. T. Connor, editor, Colonial Records of Spanish Florida, Deland, 1930, Vol. II., Manuel de Montiano, Letters of Montiano (Collections of the Georgia Historical Society, v. VII, Pt. I), Savannah 1909; Albert Manucy, "Ordnance used at Castillo de San Marcos, 1672-1834," St. Augustine, 1939.

BRITISH ORDNANCE. For detailed information John Müller, Treatise of Artillery, London, 1756, has been the basic source for eighteenth century material. William Bourne, The Arte of Shooting in Great Ordnance, London, 1587, discusses sixteenth century artillery; and the anonymous New Method of Fortification, London, 1748, contains much seventeenth century information. For colonial artillery data there is John Smith, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-Englande, and the Summer Isles, Richmond, 1819; [Edward Kimber] Late Expedition to the Gates of St. Augustine, Boston, 1935; and C. L. Mowat, East Florida as a British Province, 1763-1784, Los Angeles, 1939. Charles J. Ffoulkes, The Gun-Founders of England, Cambridge, 1937, discusses the construction of early cannon in England.

FRENCH ORDNANCE. M. Surirey de Saint-Remy, Memories d'Artillerie, 3rd edition Paris, 1745, is the standard source for French artillery material in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Col. Favé, Ètudes sur le Passé et l'Avenir de L'Artillerie, Paris, 1863, is a good general history. Louis Figurier, Armes de Guerre, Paris, 1870, is also useful.

UNITED STATES ORDNANCE. Of first importance is Louis de Tousard, American Artillerist's Companion, 2 vols., Philadelphia, 1809-13. For performance and use of artillery during the 1860's the following sources are useful: John Gibbon, The Artillerist's Manual, New York, 1863; Q. A. Gillmore, Engineer and Artillery Operations against the Defences of Charleston Harbor in 1863, New York, 1865; his Official Report . . . of the Siege and Reduction of Fort Pulaski, Georgia, New York, 1862; and the Official Records of Union and Confederate Armies and Navies. Ordnance manuals of the period include: Instruction for Heavy Artillery, U. S., Charleston, 1861; Ordnance Instructions for the United States Navy, Washington, 1866; J. Gorgas, The Ordnance Manual for the Use of the Officers of the Confederate States Army, Richmond, 1863. For United States developments after 1860: L. L. Bruff, A Text-book of Ordnance and Gunnery, New York, 1903; F. T. Hines and F. W. Ward, The Service of Coast Artillery, New York, 1910; the U. S. Field Artillery School's Construction of Field Artillery Materiel and General Characteristics of Field Artillery Ammunition, Fort Sill, 1941.

GENERAL. For the history of artillery, as well as additional biographical and technical details, there is the Field Artillery School's excellent booklet, History of the Development of Field Artillery Materiel, Fort Sill, 1941. Henry W. L. Hime, The Origin of Artillery, New York, 1915, is most useful, as is that standard work, the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1894 edition: Arms and Armour, Artillery, Gunmaking, Gunnery, Gunpowder; 1938 edition: Artillery, Coehoorn, Engines of War, Fireworks, Gribeauval, Gun, Gunnery, Gunpowder, Musket, Ordnance, Rocket, Smallarms, and Tartagila -

Events

-

2014 is the Chinese Year of the Horse

February 17, 2026 at 12am to February 5, 2027 at 12am – where & how you choose

Birthdays

Birthdays Today

Birthdays Tomorrow

Important (read & understand)

Skype: Travelingraggyman

Email and Instant Messenger:

TravelerinBDFSM @ aol/aim; hotmail; identi.ca; live & yahoo

OR

Travelingraggyman @ gmail and icq ***

1AWARD UPDATES & INFORMATION

10,000 votes - Platinum Award

5,000 votes - Gold Award

2,500 votes - Silver Award

1,000 votes - Bronze Award

300 votes - Pewter Award

100 votes - Copper Award

Member of the Associated Posting System {APS}

This allows members on various sites to share information between sites and by providing a by line with the original source it credits the author with the creation.

Legal Disclaimer

***************We here at Traveling within the World are not responsible for anything posted by individual members. While the actions of one member do not reflect the intentions of the entire social network or the Network Creator, we do ask that you use good judgment when posting. If something is considered to be inappropriate it will be removed

Site Meter

This site is strictly an artist operational fan publication, no copyright infringement intended

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries had its humble beginnings as an idea of a few artisans and craftsmen who enjoy performing with live steel fighting. As well as a patchwork quilt tent canvas. Most had prior military experience hence the name.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries.

Vendertainers that brought many things to a show and are know for helping out where ever they can.

As well as being a place where the older hand made items could be found made by them and enjoyed by all.

We expanded over the years to become well known at what we do. Now we represent over 100 artisans and craftsman that are well known in their venues and some just starting out. Some of their works have been premiered in TV, stage and movies on a regular basis.

Specializing in Medieval, Goth , Stage Film, BDFSM and Practitioner.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries a Dept of, Ask For IT was started by artists and former military veterans, and sword fighters, representing over 100 artisans, one who made his living traveling from fair to festival vending medieval wares. The majority of his customers are re-enactors, SCAdians and the like, looking to build their kit with period clothing, feast gear, adornments, etc.

Likewise, it is typical for these history-lovers to peruse the tent (aka mobile store front) and, upon finding something that pleases the eye, ask "Is this period?"

A deceitful query!! This is not a yes or no question. One must have a damn good understanding of European history (at least) from the fall of Rome to the mid-1600's to properly answer. Taking into account, also, the culture in which the querent is dressed is vitally important. You see, though it may be well within medieval period, it would be strange to see a Viking wearing a Caftan...or is it?

After a festival's time of answering weighty questions such as these, I'd sleep like a log! Only a mad man could possibly remember the place and time for each piece of kitchen ware, weaponry, cloth, and chain within a span of 1,000 years!! Surely there must be an easier way, a place where he could post all this knowledge...

Traveling Within The World is meant to be such a place. A place for all of these artists to keep in touch and directly interact with their fellow geeks and re-enactment hobbyists, their clientele.

© 2025 Created by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler.

Powered by

![]()