Traveling within the World

Linking your favorite traveling artists across the globe

In ancient times, small tablets made out of clay were used as a writing medium.

From the 4th millennium BCE in the Sumerian, Babylonian, Assyrian and Hittite civilizations of the Mesopotamia region, cuneiform characters were imprinted on a wet clay tablet with a stylus often made of reed. Once written upon, many tablets were dried in the sun or air, remaining fragile. Later, these unfired clay tablets could be soaked in water and recycled into new clean tablets. Other tablets, once written, were grilled in a kennal or fired in kilns (or inadvertently, when buildings were burnt down by accident or during conflict) making them hard and durable. Collections of these clay documents made up the very first archives. They were at the root of first libraries. Tens of thousands of written tablets, including many fragments, have been found in the Middle East.

The Tărtăria tablets, thought to be from the Danubian civilization, may be older still, having been carbon dated to before 4000 BCE, and possibly dating from as long ago as 5500 BCE, but their interpretation remains controversial.

In the Minoan/Mycenaean civilizations, writing has not been observed for any use other than accounting. Tablets serving as labels, with the impression of the side of a wicker basket on the back, and tablets showing yearly summaries, suggest a sophisticated accounting system. In this cultural region the tablets were never fired deliberately, as the clay was recycled on an annual basis. However, some of the tablets were "fired" as a result of uncontrolled fires in the buildings where they were stored. The rest are still tablets of unfired clay, and extremely fragile; some modern scholars are investigating the possibility of firing them now, as an aid to preservation.

Wax tablet

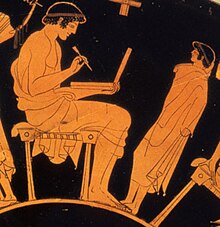

A wax tablet (cera) is a tablet made of wood and covered with a layer of wax, often linked loosely to a cover tablet, as a "double-leaved" diptych. It was used as a reusable and portable writing surface in Antiquity and throughout the Middle Ages. Cicero's letters make passing reference to the use of cerae, and some examples of wax-tablets have been preserved in waterlogged deposits in the Roman fort at Vindolanda on Hadrian's Wall. Medieval wax tablet books are on display in several European museums.

Technology and applications

Writing on the wax surface was performed with a pointed instrument, a stylus. Writing by engraving in wax required the application of much more pressure and traction than would be necessary with ink on parchment or papyrus, and the scribe had to lift the stylus in order to change the direction of the stroke. Therefore the stylus could not be applied with the same degree of dexterity as a pen. A straight-edged, spatula-like implement (often placed on the opposite end of the stylus tip) would be used in a razor-like fashion to serve as an eraser. The entire slate could be erased for reuse by warming it to about 50 °C and smoothing the softened wax surface. The modern expression, of "a clean slate" is related to the Latin expression "tabula rasa".

Wax tablets were used for a variety of purposes, from taking down students' or secretaries' notes to recording business accounts. Early forms of shorthand were used too.

Use in antiquity

The first appearance of writing tablets in written Greek appears in Homer— an Homeric example[2] in which writing is referred to — in the narrated tale of Bellerophon (Iliad vi.155–203) which introduces the trope of the "fatal" or "Bellerophontic" letter, with its message sealed within the folded tablets: "Kill the bearer of this". Other examples of early writing survived through Parallel Lives of Plutarch and Hyginus (Fabulae). In "Theseus", a "love letter" written by Theseus is presented to Ariadne. Plutarch goes on to describe how Theseus erected a pillar on the Isthmus of Corinth, which bears an inscription of two lines. Before the decipherment of Linear B by Michael Ventris the written tablets in the Iliad were considered an anachronism.

The Greeks started using the folding pair of wax tablets, along with the leather scroll in the mid-eighth century. Liddell & Scott, 1925, derive the word for the writing-tablet, deltos (δέλτος), from the letter delta (Δ) and based on ancient Greek and Roman authors and scripts they propose an old shape of tablets to account for it. An alternative theory (Burkert 1992:30) holds that it has retained its Semitic designation, daltu, which originally signified "door" but was being used for writing tablets in Ugarit in the thirteenth century BCE. In Hebrew the term evolved into daleth. In the second millennium BCE writing tablets were in use in Mesopotamia as well as Syria and Palestine: "the find of one exemplar in the fourteenth-century wreck at Ulu Burun near Kaş, Turkey, is considered sensational, even if no trace of the writing for which it was used is preserved." (Burkert 1992:30) Writing tablets of ivory have appeared in the ruins of Sargon's palace in Nimrud and, in the form of richly carved ivory diptychs deriving from the consular diptychs, remained a traditional Roman elite gift on the occasion of accession to high office into Byzantine times.

Use in medieval to modern times

Hériman of Tournai (1095 — 1147), a monk of the abbey of St Martin of Tournai, said that his history was long in gestation: as a boy. he says, "I even wrote down a certain amount on tablets".

A remarkable example of a wax tablet book are the servitude records which the hospital of Austria's oldest city, Enns, established in 1500. Ten wooden plates, sized 375 x 207 mm and arranged in a 90 mm stack, are each divided into two halves along their long axis. The annual payables due are written on parchment or paper glued to the left sides. Payables received were recorded for deduction (and subsequently erased) on the respective right sides, which are covered with brownish-black writing wax. The material is based on beeswax, and contains 5-10% plant oils and carbon pigments; its melting point is about 65 °C. This volume is the continuation of an earlier one, which was begun in 1447.

Wax tablets were used for high-volume business records of transient importance until the 19th century. For instance, the salt mining authority at Schwäbisch Hall employed wax records until 1812. The fish market in Rouen used them even until the 1860s, where their construction and use has been well documented in 1849

The Vindolanda tablets are fragments of wooden leaf-tablets with writing in ink found at Vindolanda Roman fort in northern England.The tablets date from the first and second centuries AD, which makes them roughly contemporary with Hadrian's Wall, which is near Vindolanda. The tablets contain messages to and from members of the garrison of Vindolanda, their families, and their slaves. Similar records on papyrus were known from elsewhere in the Roman Empire, but wooden tablets had not been recovered until archaeologist Robin Birley discovered them at Vindolanda in 1973. Pages have since been found at Carlisle, Cumbria, and continue to be found at Vindolanda.

Most of the tablets are official military documents. However, the best-known document is perhaps Tablet 291, written around 100 AD from Claudia Severa, the wife of the commander of a nearby fort, to Sulpicia Lepidina, wife of the commandant of Vindolanda, inviting her to a birthday party. The invitation is one of the earliest known examples of writing in Latin by a woman. It has even been claimed that this is the earliest surviving letter known to be written by a woman in any language.

The tablets are written in Roman cursive script and throw light on the extent of literacy in Roman Britain. One of the tablets confirms that Roman soldiers wore underpants (subligaria), and also testifies to a high degree of literacy in the Roman army.

The tablets do not throw much light on the indigenous population, but there are references. Until the discovery of the tablets, historians could only speculate on whether the Romans had a nickname for the Britons. "Brittunculi" (diminutive of Britto; hence 'little Britons') found on one of the Vindolanda tablets, is now known to be a derogatory, or patronizing, term used by the Roman garrisons that were based in Northern Britain to describe the locals.

Conservation and impact

The tablets were originally preserved in waterlogged soil and are delicate.

The tablets are held at the British Museum, where a selection of them is on display in its Roman Britain gallery (Room 49).

The tablets featured in the list of British archaeological finds selected by experts at the British Museum for the 2003 BBC Television documentary Our Top Ten Treasures. Viewers were invited to vote for their favourite and the tablets came top of the poll.

In 2009 it was reported that the Museum at Vindolanda had secured funding for an upgrade so that a selection of tablets on loan from the British Museum can be displayed at the site where they were found.The British Museum already loans other objects in its Partnership UK Scheme, although it argues that the "restitutionist premise, that whatever was made in a country must return to an original geographical site, would empty both the British Museum and the other great museums of the world"

A tabula ansata or tabella ansata (Latin for tablet with handles, plural tabulae ansatae or tabellae ansatae) is a tablet with dovetail handles. It was a favorite form for votive tablets in imperial Rome.

Tabulae ansatae identifying soldiers' units have been found on the tegimenta (leather covers) of shields, for example in Vindonissa (Windisch, Switzerland). Sculptural evidence, for example on the metopes from the Tropaeum Traiani (Adamclisi, Romania), shows that they were also used for the same purpose on the shields.

Tabulae ansatae have been used by modern artists as early as the 15th century, as shown on the tomb of Charles, Count of Maine attributed to Francesco Laurana, in Le Mans Cathedral.[5] The Statue of Liberty is holding one such tablet on which "July 4th 1776" is inscribed using Roman numerals.

A tablet, in the religious context, is a term traditionally used for religious texts.

Jews and Christians believe that Moses brought the Ten Commandments from Mount Sinai in the form of two stone tablets. According to the Book of Exodus, God delivered the tablets twice, the first set having been smashed by Moses in his anger at the idol-worship of the Israelites. The first set contained the detailed instructions for the construction of the Tabernacle, the making of priestly vestments, etc; the replacement set contained the Ritual Decalogue, one of the three versions of the Ten Commandments given in the Old Testament.

Muslims believe that the divine destiny is when God wrote down in the Preserved Tablet ("al-Lawhu 'l-Mahfuz") all that has happened and will happen, which will come to pass as written. The term is also used as part of the title of many shorter works of Bahá'u'lláh, founder of the Bahá'í Faith, and his son and successor `Abdu'l-Bahá.

|

|

| Material | Wood |

|---|---|

| Size | Length: 182 mm (7.2 in) |

| Writing | Latin |

| Created | 1stC (late)-2ndC (early) |

| Period/culture | Romano-British |

| Place | Vindolanda |

| Present location | Room 49, British Museum, London |

| Registration | 1989,0602.74 |

Tags:

Replies to This Discussion

Events

-

2014 is the Chinese Year of the Horse

February 17, 2026 at 12am to February 5, 2027 at 12am – where & how you choose

Birthdays

Birthdays Today

Birthdays Tomorrow

Important (read & understand)

Skype: Travelingraggyman

Email and Instant Messenger:

TravelerinBDFSM @ aol/aim; hotmail; identi.ca; live & yahoo

OR

Travelingraggyman @ gmail and icq ***

1AWARD UPDATES & INFORMATION

10,000 votes - Platinum Award

5,000 votes - Gold Award

2,500 votes - Silver Award

1,000 votes - Bronze Award

300 votes - Pewter Award

100 votes - Copper Award

Member of the Associated Posting System {APS}

This allows members on various sites to share information between sites and by providing a by line with the original source it credits the author with the creation.

Legal Disclaimer

***************We here at Traveling within the World are not responsible for anything posted by individual members. While the actions of one member do not reflect the intentions of the entire social network or the Network Creator, we do ask that you use good judgment when posting. If something is considered to be inappropriate it will be removed

Site Meter

This site is strictly an artist operational fan publication, no copyright infringement intended

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries had its humble beginnings as an idea of a few artisans and craftsmen who enjoy performing with live steel fighting. As well as a patchwork quilt tent canvas. Most had prior military experience hence the name.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries.

Vendertainers that brought many things to a show and are know for helping out where ever they can.

As well as being a place where the older hand made items could be found made by them and enjoyed by all.

We expanded over the years to become well known at what we do. Now we represent over 100 artisans and craftsman that are well known in their venues and some just starting out. Some of their works have been premiered in TV, stage and movies on a regular basis.

Specializing in Medieval, Goth , Stage Film, BDFSM and Practitioner.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries a Dept of, Ask For IT was started by artists and former military veterans, and sword fighters, representing over 100 artisans, one who made his living traveling from fair to festival vending medieval wares. The majority of his customers are re-enactors, SCAdians and the like, looking to build their kit with period clothing, feast gear, adornments, etc.

Likewise, it is typical for these history-lovers to peruse the tent (aka mobile store front) and, upon finding something that pleases the eye, ask "Is this period?"

A deceitful query!! This is not a yes or no question. One must have a damn good understanding of European history (at least) from the fall of Rome to the mid-1600's to properly answer. Taking into account, also, the culture in which the querent is dressed is vitally important. You see, though it may be well within medieval period, it would be strange to see a Viking wearing a Caftan...or is it?

After a festival's time of answering weighty questions such as these, I'd sleep like a log! Only a mad man could possibly remember the place and time for each piece of kitchen ware, weaponry, cloth, and chain within a span of 1,000 years!! Surely there must be an easier way, a place where he could post all this knowledge...

Traveling Within The World is meant to be such a place. A place for all of these artists to keep in touch and directly interact with their fellow geeks and re-enactment hobbyists, their clientele.

© 2024 Created by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler.

Powered by

![]()