Traveling within the World

Linking your favorite traveling artists across the globe

period style medical equipment

Replies to This Discussion

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on January 19, 2012 at 1:29pm

-

Medieval Medicine

Medieval Medicine History

There are two distinct periods in the history of Medieval Medicine. The first concerns the early stages, from the 6th Century to the 9th Century, and is occupied mainly with the contributions to the Medieval Medicine made by those who were still in touch with the old Greek writers; while the second represents the early Renaissance, when the knowledge of the Greek writers was gradually filtering back again, sometimes through the uncertain channel of the Arabic.The real history of Medieval Medicine—that is, of scientific medicine—is eclipsed by the story of popular medicine. So much has been said of the medical superstitions, many of which were rather striking, that comparatively little space has been left for the serious medical science and practice of the time, which contain many extremely interesting details. When we turn our attention away from this popular pseudo-history of Medieval Medicine, which has unfortunately led so many even well informed persons into entirely wrong notions with regard to medical progress during an important period, we find much that is of enduring interest.

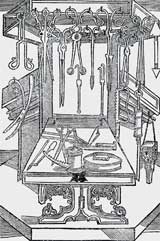

Brunschwig's Surgical Armamentarium

Brunschwig's Surgical ArmamentariumThe first documents that we have in the genuine history of Medieval Medicine, after the references to the organizations of Christian hospitals at Rome and Asia Minor in the 4th and 5th centuries, are to be found in the directions provided in the rules of the religious orders for the care of the ailing. St. Benedict (480—543), the founder of the monks of the West, was particularly insistent on the thorough performance of this duty.

One of the rules of St. Benedict required the Abbot to provide in the monastery an infirmary for the ailing, and to organize particular care of them as a special Christian duty. The wording of the rule in this regard is very emphatic. “ The care of the sick is to be placed above and before every other duty, as if, indeed, Christ were being directly served in waiting on them. It must be the peculiar care of the Abbot that they suffer from no negligence. The Infirmarian must be thoroughly reliable, known for his piety and diligence and solicitude for his charge.” The last words of the rule are characteristic of Benedict’s appreciation of cleanliness as a religious duty, though doubtless also the curative effect of water was in mind. “Let baths be provided for the sick as often as they need them.” Cassiodorus (468—560), who had been the prime minister of the Ostrogoth Emperors, had his rule founded on that of the Benedictines. He promoted the herbal medicine, by recommending to learn the nature of herbs, and study diligently the way to combine their various species for human health; but he advised to not place your entire hope on herbs, nor seek to restore health only by human counsels. Since medicine has been created by God, and since it is He who gives back health and restores life, turn to Him.

The monasteries are thus seen to have been in touch with Greek medicine from the earliest medieval times. The other important historical documents relating to Medieval Medicine which we

possess concern the work of the men born and brought up in Asia Minor, for whom the Greeks were so close as to be living influences. Aëtius, Alexander of Tralles, and Paul of Egina have each written a series of important chapters on medical subjects, full of interest because the writers knew their Greek classic medicine, and were themselves making important observations.Medieval Medicine Schools

The first medical school of modern history, and the institution which more than any other has helped us to understand the Medieval Medicine, is that of Salerno, formally organized in the 10th Century but founded a century earlier, and reaching a magnificent climax of development at the end of the 12th Century. Anyone who might be tempted to think that Medieval medicine was not taken seriously, or that careful clinical observations and serious experiments for the cure of disease were not made at Salerno, will be amply undeceived by the reading of De Renzi. Above all, he makes it very clear that medical education was taken up with rigorous attention to details and high standards maintained. Three years of college work were demanded in preparation for medical studies, and then four years of medicine, followed by a year of practice with a physician, and even an additional year of special study in anatomy, had to be taken, if surgery was to be

practiced. All this before the license to practice medicine was given.Probably the best way to convey in brief form a good idea of the teaching in Medieval medicine at Salerno is to quote the Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum, the Code of Health of the School of Salernum, which for many centuries was so popular in Europe. The Regimen was written in the rhymed verses which were so familiar at this time. It was not written for physicians, but for popular information, and it seems to have been a compilation of maxims of health from various professors of the Salernitan School. From the Code, we find that the medieval hygienists believed very much in early rising, cold water, thorough cleansing, exercise in the open air, yet without sudden cooling afterwards.

The Salernitan writers were not believers in noonday sleep, though one might have expected that the tradition of the siesta in Italy had been already established. They insist that it makes one feel worse rather than better to break the day by a sleep at noonday. They believed in light suppers, and with regard to the interval between meals, the rule was, wait until your stomach is surely empty. Pure air and sunlight were favorite tonics. The tradition with regard to the difficulty of the digestion of pork, had already been established. The digestibility of pork could, however, be improved by good wine. Milk for consumptives was a favorite recommendation. The tradition had come down from very old times, and Galen insisted that fresh air and milk and eggs was the best possible treatment for consumption. The Salernitan physicians recommended various kinds of milk, goat’s, camel’s, and sheep’s milk as well as cow’s. The Regimen warned, however, that milk will not be good if it produces headache or if there is fever. They recommended the various simples, mallow, mint, sage, rue, the violet for headache and catarrh, the nettle, mustard, hyssop, elecampane, pennyroyal, cresses, celandine, saffron, leeks—a sovereign remedy for sterility—pepper, fennel, vervaine, henbane, and others.

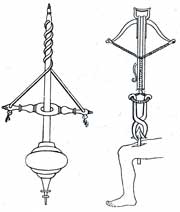

Surgical Instruments of Guy de Chauliac-

Surgical Instruments of Guy de Chauliac-

On the right, a balista for extraction of arrowsOne very interesting contribution to medical literature that comes to us from Salerno bears the title “The Coming of a Physician to His Patient, or an Instruction for the Physician Himself.” It illustrates very well the practical nature of the teaching of Salerno, and gives a rather vivid picture of the medical customs of the time.

The next great medical school contributing to the development of Medieval Medicine was that of Montpellier in the South of France. Montpellier, situated not far from the Mediterranean, came to be a health resort. Patients flocked to it from many countries of the West of Europe; physicians settled there because patients were numerous, and medical instruction came to be offered to students. Fame came to the school. The fundamental reason for this striking development of the intellectual life seems to have been that Montpellier was not far from Marseilles, which had been a Greek colony originally and continued to be under Greek influence for many centuries. As a consequence of this the artistic and intellectual life of the southern part of France was higher during the earlier Middle Ages than that of any other part of Europe, except certain portions of South Italy.

A number of men who are famous in the history of Medieval Medicine made their medical studies at Montpellier in the 12th and 13th centuries. Among them are Mondeville, who afterwards taught surgery at Paris; and Guy de Chauliac, who was a Papal Physician at Avignon and at the same time a professor at Montpellier, probably spending a certain number of weeks, or perhaps months, each year in the university town. One of the distinguished professors at Montpellier was the well-known Arnold de Villanova, of whose name there are a number of variants, including even Rainaldus and Reginaldus. A very well-known teacher who has had a reputation in English speaking countries because his name was supposed to indicate that he was a Scotsman, was Bernard Gordon or de Gordon, whose name is, however, also written Gourdon. He was a teacher at Montpellier at the end of the 13th Century and the beginning of the 14th Century.Montpellier represented for the West of Europe then very nearly what Salerno did for Italy and Eastern Europe. It very probably attracted many English and Scottish students of medicine. It has survived, however, while Salerno disappeared as an education force.

Medieval Medicine in the latter Middle Ages

The Medieval Medicine in the later Middle Ages, that is, to the middle of the 15th Century, was greatly influenced by the medical schools which arose in Italy and the West of Europe during this period. These were organized mainly in connection with universities, Salerno, Montpellier, Bologna, Paris, Padua, in the order of their foundations, so far as they can be ascertained. These university medical schools represented serious scientific teaching in medicine, and certainly were not more prone to accept absurdities of therapeutics and other phases of supposed medical knowledge than have been the universities of any other corresponding period of time. There were a number of Arabian and Jewish physicians who made a deep impression on the medicine of the later Middle Ages. Maimonides (1135-1204) was one of the Jews physicians who anticipated the rule for taking fruits before meals, and so often as fruit cocktails at the beginning of other meals. He thought that grapes, figs, melons, should be taken before meals, and not mixed with other food. He set down as a rule that what was easily digestible should be eaten at the beginning of the meal, to be followed by what was more difficult of digestion. He declared it to be an axiom of medicine “ that so long as a man is able to be active and vigorous, does not eat until he is over full, and does not suffer from constipation, he is not liable to disease.”

As a rule of the Medieval Medicine, the physicians trusted nature much more than did their colleagues of modern history—that is, after the Renaissance until the present epoch of medical science began. The most interesting feature of the work of the North Italian surgeons of the later Middle Ages is their discovery and development of the two special advances of our modern surgery. These are, union by first intention, and anesthesia.

The North Italian surgeons replaced the use of ointments by wine, and evidently realized its cleansing —that is, antiseptic—quality. What is often not realized is, that the very old traditional treatment of wounds by the pouring of wine and oil into them represented a mild antiseptic and a soothing protective dressing. The wine inhibited the growth of ordinary germs, the oil protected the wound from dust and dirt. They were not ideal materials for the purpose, but they were much better when discreetly used than many surgical dressings of much more modern times founded on elaborate theories.Anesthesia is perhaps an even greater surprise of the Medieval Medicine than practical antisepsis. A great many of the surgeons of the time seem to have experimented with substances that might produce anesthesia. Mandragora was the base of most of these anesthetics, though a combination with opium seems to have been a favorite. They succeeded apparently, even with such crude means, in producing insensibility to pain without very serious dangers. One of the methods of Da Lucca was by inhalation, and seems to have been in use for a full century. Also, Guy de Chauliac, in the 14th Century, describes the method as it was used in his day. He well deserves the name of father of modern surgery. He was educated in a little town in the South of France, and made his medical studies at Montpellier.

In the 15th Century Germany, Hans von Gerssdorff and Hieronymus Brunschwig, have both left early printed treatises on Surgery which give excellent woodcuts showing pictures of instruments, operations, and costumes.

Medieval Medicine and plastic surgery

A very interesting development of Medieval Medicine and which probably will be least expected, was in plastic surgery. In the first half of the 15th Century, the two Branca, father and son, performed a series of successful operations for the restoration of the nose particularly, and the son invented a series of similar procedures for the restoration of mutilated lips and ears. The father seems to have built up the nose from other portions of the face, possibly using, as Gurit suggests, the skin of the forehead.

Medieval Medicine and oral surgery

Characteristic for the Medieval Medicine of the later Middle Ages is the inclusion in the textbooks of surgery of remarks on oral surgery, and suggestions of treatment for the various diseases of the teeth. Guy de Chauliac in “La Grande Chirurgie “ lays down certain rules for the preservation of the teeth, and shows that the ordinary causes of dental decay were well recognized in his time. Emphasis was laid by him on not taking foods too hot or too cold, and above all on the advisability of not having either hot or cold food followed by something very different from it in temperature. The breaking of hard things with the teeth was warned against as responsible for such fissures in the enamel as gave opportunity for the development of decay. The eating of sweets, and especially the sticky sweets, preserves, and the like, were recognized as an important source of caries. The teeth were supposed to be cleaned frequently, and not to be cleaned too roughly, for this would do more harm than good.

Chauliac is particularly emphatic in his insistence on not permitting alimentary materials to remain in the cavities, and suggests that if cavities between the teeth tend to retain food material they should even be filled in such a way as to prevent these accumulations. His directions for cleansing the teeth were rather detailed. His favorite treatment for wounds was wine, and he knew that he succeeded by means of it in securing union by first intention. It is not surprising, then, to find that he recommends rinsing of the mouth with wine as a precaution against dental decay. A vinous decoction of wild mint and of pepper he considered particularly beneficial, though he thought that dentifrices, either powder or liquid, should also be used. He seems to recommend the powder dentifrices as more efficacious.

His favorite prescription for a tooth-powder was more elaborate. He took equal parts of cuttle-bones, small white seashells, pumice-stone, burnt stag’s horn, nitre, alum, rock salt, burnt roots of iris, aristoloehia, and reeds. All of these substances should be carefully reduced to powder and then mixed.

His favorite liquid dentifrice contained the following ingredients: Half a pound each of sal ammoniac and rock salt, and a quarter of a pound of saccharin alum. All these were to be reduced to powder and placed in a glass alembic and dissolved. The teeth should be rubbed with it, using a little scarlet cloth for the purpose. Just why this particular color of cleansing cloth was recommended is not quite clear. Guy de Chauliac was also interested in mechanical dentistry and the artificial replacement of lost teeth.Medieval Medicine and women in medical studies

The most interesting feature of Medieval Medicine development is that, from the 12th to the 14th centuries, the application of women to medical studies was distinctly encouraged, and we find evidence that a number of women studied and taught medicine, wrote books on medical subjects, were consulted with regard to medico-legal questions, and in general were looked upon as medical colleagues in practically every sense of the word. The very first medical school that developed in the medieval times, that of Salerno, was quite early in its history opened to women students, and a number of women professors were on its faculty.

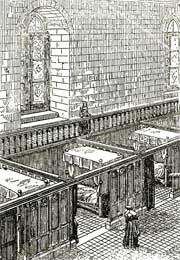

13th Century Medieval Hospital (Tonerre)

13th Century Medieval Hospital (Tonerre)The Benedictines were already habituated to the idea that women were quite capable, if given the opportunity, of taking advantage of the highest education; and besides, they were accustomed to see them occupied, and successfully, with the care of the ailing. In the Benedictine convents for women, as they spread throughout Italy—and afterwards throughout Germany, and France, and England—the intellectual life was pursued as faithfully as the spiritual. Probably the most important book of Medieval medicine that we have from the 12th Century is written by a Benedictine Abbess, Hildegard von Bingen, also known as St. Hildegarde.

Medieval Medicine and the hospitals

The development of Medieval Medicine led to the development of hospitals, and we have abundant evidence of the existence of fine hospitals in the Middle Ages. Historical traditions from the earlier as well as the later medieval times demonstrate a magnificent development of hospital organization. The hospitals in the larger towns at least were model hospitals in many ways, and ever so much better than many hospital structures erected in post-medieval centuries. The hospitals built in the 13th Century usually were of one story, had high ceilings with large windows, often were built near the water in order that there might be abundance of water for cleansing purposes, and also so that the sewage of the hospital might be carried off, and had tiled floors that facilitated thorough cleansing. Viollet le Duc, in his “Dictionary of Architecture,” has given a picture of the interior of one of these medieval hospitals, that of Tonerre in France, erected by Marguerite of Bourgogne, the sister of St. Louis, in 1293, and reproduced here.

-

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on January 19, 2012 at 1:29pm

-

Surgical set 2

Surgical set 2 Century, sources:

Century, sources:

Ancient and medieval archeological finds, Preci (Italy) S.Eutizio abbey.

Materials:

Materials:

iron, wood, brass

Sizes:

Sizes:

A-cauterising irons

lengh.35cm

B- fleam & bowl

lengh.28cm

C-medical spoon

lengh.14cm

D- arrow remover

lengh.20cm

Surgical set 1

Surgical set 1

€ 180.00

Surgical set

Surgical set Century, sources:

Century, sources:

Ancient and medieval archeological finds, Preci (Italy) S.Eutizio abbey. Livre de Chirurgie end of 15th cent.

Materials:

Materials:

iron, wood

Sizes:

Sizes:

A - cm 15; B - cm 17; c - cm 17

A - saw - 30 cm

B - needle set - 4-5-6-7 cm

C - clamp 1 - 21 cm

D - clamp 2 - 22 cm

E - hook - 23 cm

F - double hook - 23 cm

G - probe - 20 cm

H - bistoury 1 - 16 cm

I - bistoury 2 - 15 cm

Surgical set

Surgical set

€ 250.00 -

-

Permalink Reply by Dept of PMM Artists & things on January 19, 2012 at 1:30pm

-

Hildegard Von Bingen's Physica Translation by Priscilla Throop ISBN 0892816619

A very interesting account of the use of materials and how they were used in treatments and how they connected to the medieval philosophy of medicine

The Medieval Surgery by Tony Hunt - ISBN 0851157548

An excellent pictorial example of procedures with brief explanations - invaluable!

The Trotula: an English translation of the Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine

ISBN 0812218086

An excellent example of the medieval knowledge base - very worth the read, but not apt as a man you would not want to deal with many of the aspects of the book, so you would remain free from the contaminations the woman and original sin!

Medieval Medicine in Illuminated Manuscripts

By Peter Murray Jones Hardcover 112 pages (December 1998) Publisher: British Library Publishing Division

ISBN: 0712306579

This book is an excellent source of pictorial evidence for medical equipment and anecdotal information on medical treatments of the time.

Medicine and Society in Later Medieval England (Sutton Illustrated History Paperbacks)

By Carole Rawcliffe Paperback 241 pages (October 23, 1997) Publisher: Sutton Publishing

ISBN: 0750914971

This is a very well written and easy to understand guide to medicine in England during our period and I would recommend it, as it is highly informative of medicine in medieval society.

Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: Introduction to Knowledge and Practice

By Nancy G. Siraisi Paperback 264 pages (June 1, 1990) Publisher: University of Chicago Press

ISBN: 0226761304

Very academic!

Later but still very interesting medicinal books

The Surgeons Mate 1617 by John Woodall: Surgeon General to the East India Company ISBN 0906230152 Which is a copy of the original printed text,

Kill or Cure: Medical Remedies of the 16th and 17th Centuries from the Staffordshire Records Office ISBN 0946602166 -

Events

-

2014 is the Chinese Year of the Horse

February 17, 2026 at 12am to February 5, 2027 at 12am – where & how you choose

Birthdays

Birthdays Today

Birthdays Tomorrow

Important (read & understand)

Skype: Travelingraggyman

Email and Instant Messenger:

TravelerinBDFSM @ aol/aim; hotmail; identi.ca; live & yahoo

OR

Travelingraggyman @ gmail and icq ***

1AWARD UPDATES & INFORMATION

10,000 votes - Platinum Award

5,000 votes - Gold Award

2,500 votes - Silver Award

1,000 votes - Bronze Award

300 votes - Pewter Award

100 votes - Copper Award

Member of the Associated Posting System {APS}

This allows members on various sites to share information between sites and by providing a by line with the original source it credits the author with the creation.

Legal Disclaimer

***************We here at Traveling within the World are not responsible for anything posted by individual members. While the actions of one member do not reflect the intentions of the entire social network or the Network Creator, we do ask that you use good judgment when posting. If something is considered to be inappropriate it will be removed

Site Meter

This site is strictly an artist operational fan publication, no copyright infringement intended

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries had its humble beginnings as an idea of a few artisans and craftsmen who enjoy performing with live steel fighting. As well as a patchwork quilt tent canvas. Most had prior military experience hence the name.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries.

Vendertainers that brought many things to a show and are know for helping out where ever they can.

As well as being a place where the older hand made items could be found made by them and enjoyed by all.

We expanded over the years to become well known at what we do. Now we represent over 100 artisans and craftsman that are well known in their venues and some just starting out. Some of their works have been premiered in TV, stage and movies on a regular basis.

Specializing in Medieval, Goth , Stage Film, BDFSM and Practitioner.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries a Dept of, Ask For IT was started by artists and former military veterans, and sword fighters, representing over 100 artisans, one who made his living traveling from fair to festival vending medieval wares. The majority of his customers are re-enactors, SCAdians and the like, looking to build their kit with period clothing, feast gear, adornments, etc.

Likewise, it is typical for these history-lovers to peruse the tent (aka mobile store front) and, upon finding something that pleases the eye, ask "Is this period?"

A deceitful query!! This is not a yes or no question. One must have a damn good understanding of European history (at least) from the fall of Rome to the mid-1600's to properly answer. Taking into account, also, the culture in which the querent is dressed is vitally important. You see, though it may be well within medieval period, it would be strange to see a Viking wearing a Caftan...or is it?

After a festival's time of answering weighty questions such as these, I'd sleep like a log! Only a mad man could possibly remember the place and time for each piece of kitchen ware, weaponry, cloth, and chain within a span of 1,000 years!! Surely there must be an easier way, a place where he could post all this knowledge...

Traveling Within The World is meant to be such a place. A place for all of these artists to keep in touch and directly interact with their fellow geeks and re-enactment hobbyists, their clientele.

© 2025 Created by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler.

Powered by

![]()