Traveling within the World

Linking your favorite traveling artists across the globe

By Alfred Leix

Mediaeval civilization may be divided into two distinct parts, the first ending with the 12th century, and the second comprising the 13th and 14th centuries. The early period produced the severe and massive style of architecture known as Romanesque or, in England, Norman, while the later period lives on in the soaring beauty of the Gothic style. Equally marked are the differences in everyday life. Book-illustrations and painted sculpture tell us that the dress of the early Middle Ages was coarse, giving preference to wool and linen, frieze and leather, whereas that of the later period was gay and costly. The age of chivalry, of courtly custom and courtly love, appreciated to the full the aesthetic value of refinement and taste.

Mediaeval civilization may be divided into two distinct parts, the first ending with the 12th century, and the second comprising the 13th and 14th centuries. The early period produced the severe and massive style of architecture known as Romanesque or, in England, Norman, while the later period lives on in the soaring beauty of the Gothic style. Equally marked are the differences in everyday life. Book-illustrations and painted sculpture tell us that the dress of the early Middle Ages was coarse, giving preference to wool and linen, frieze and leather, whereas that of the later period was gay and costly. The age of chivalry, of courtly custom and courtly love, appreciated to the full the aesthetic value of refinement and taste.

In former days cloth was spun and woven at home, from home-grown flax or the wool of native sheep, and dyed with extracts from native plants. Foreign dyes were to a certain extent imported, but into Italy and England, rather than to Germany, and that only occasionally as yet. Costly stuffs and articles of dress were, however, imported readymade. During the later period, parti-coloured dress came into vogue, consisting of perhaps, a doublet in two colours with similar hose where the right leg might match the left half of the doublet and vice versa. It was not without reason that the dyer's craft began to flourish at this time.

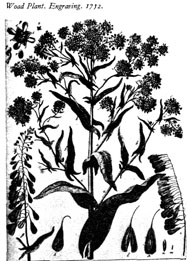

To trace the history of dyeing in the Middle Ages is to make an interesting study of the progress of refinement generally. In the 43rd Chapter of the instructions concerning the administration of his lands, Charlemagne decreed that not only flax and wool, but also "waisdo, vermiculo, varentia", that is, woad, cochineal dye, and madder should be produced. Woad was the most important dye of the Middle Ages. It might be described as a universal dye. The richness of the shade achieved depended on the quality and quantity of the woad used, and on the frequency with which the cloth was immersed in the bath. Thus a fresh bath would be used for dyeing black, then, as the solution grew weaker, for blue and, finally, green. By the addition of madder a species of purple was attained. The principal woad-growing districts were Saxony and Thuringia, whose wealth actually was based on this plant. In Thuringia it was proverbial that the woadfields were the country's gold and silver mines. Erfurt and Naumburg were the centres.

To trace the history of dyeing in the Middle Ages is to make an interesting study of the progress of refinement generally. In the 43rd Chapter of the instructions concerning the administration of his lands, Charlemagne decreed that not only flax and wool, but also "waisdo, vermiculo, varentia", that is, woad, cochineal dye, and madder should be produced. Woad was the most important dye of the Middle Ages. It might be described as a universal dye. The richness of the shade achieved depended on the quality and quantity of the woad used, and on the frequency with which the cloth was immersed in the bath. Thus a fresh bath would be used for dyeing black, then, as the solution grew weaker, for blue and, finally, green. By the addition of madder a species of purple was attained. The principal woad-growing districts were Saxony and Thuringia, whose wealth actually was based on this plant. In Thuringia it was proverbial that the woadfields were the country's gold and silver mines. Erfurt and Naumburg were the centres.

In Silesia, too, woad was grown, but not enough to supply the needs of that area, whereas Saxony and Thuringia were export countries. How truly enormous the output was, is demonstrated by the fact that in Gšrlitz alone it amounted, in 1477, to 9000 measures valued at 360,000 guilders. In the 14th century the quantity used at Nuremberg is given as 103, in the 15th century, as au waggon-loads. In Thuringia woad was grown in more than 300 villages, to the value of at least 450,000 Meissen guilders. One merchant of Erfurt sold 125,000 guilders worth of woad in 1617. It was exported to all the important weaving centres, especially to Flanders. Antwerp imported large quantities. Very considerable amounts appear to have found their way to England in the 14th and 15th centuries, through the medium of the Hanse. France too, supplied England with woad already in the early Middle Ages, and in 1420 imports of coccus polonicus for scarlet dyeing are reported. The mediaeval merchant's life was not without its dangers. Accidents on the roads were frequent, and highway robbery by no means a rare occurrence. We owe our accurate knowledge of the value of various dyes to the claims for damages presented by merchants whose goods had fallen into the hands of privateers. In times of war it was the custom of both parties to grant letters of marque. Trade with England suffered very much from this legitimate nuisance. Nevertheless, England was an important customer for Germany in the woad trade as late as the 17th century, though it was by that time not only a woad-growing country itself, but also imported indigo, a practice supported by the government at the expense of the native woad production.

It was indigo which finally crushed the woad trade, in spite of every imaginable obstacle placed in its way. The use of indigo was forbidden by law, and the report put about that it ruined the texture of the cloth. Bitter complaints were voiced, that "gold was given to the Dutch for a worthless dye, while the woad industry of Thuringia was allowed to fall into decay". It was of no avail, indigo won the day. Madder-growing however, held its own until the 19th century. This brilliant red dye, made from the roots of rubia tinctorum, was known to the ancients, and also used in various forms in the East. It was exceedingly popular in Europe, in fact, the principal red dye. In the 13th century its cultivation already yielded a considerable revenue in taxes and duties. Madder was grown practically all over Germany, and exported in large quantities, from Magdeburg to Poland in the 14th, and to Flanders, Italy, and England in the 15th century. Norwich appears to have been an important English centre of the trade, as the name of one of its streets, Madder Market, would seem so suggest.

The production of the scarlet dye habitually used, was less easy. It was actually gained from a species of parasite, the cochineal insect, picked from the plants by serfs. The exports of this dye from Germany to Flanders were considerable, and a Venetian authority esteems its quality more highly than that of the Levantine product.

The end of the Middle Ages is foreshadowed by the preponderance of imported dye stuffs. Nearly all of these were known to the Middle Ages, but very rarely used, probably because of the prohibitive costs. It was not until the discovery of the passage to India made imports on a large scale possible, without the heavy costs of intermediary trade, that they really became popular, especially as the same dyes were found to occur in America. The dyes in question were brazil-wood, orseille, saffron, and safflor, as well as lacmus and indigo.

Only the most important of these can find mention here. Brazil-wood, the wood of caesalpina sappan, is mentioned in 1321, and then frequently about 1400. It came from Sumatra, Ceylon, and India, via Venice, where it was valued in 1409 at 28-36 ducats per cwt. In America it was found in such quantities that a whole country received the name of Brazil.

The dyeing qualities of orseille are said to have been discovered in about 1300 by a Florentine merchant, whose family was called Ruccellai after it. It seems more probable that he became acquainted with the dye in the Levant and then found it again in Italy. After the conquest of the Canary Islands, the dye was imported from there straight to Germany. Lichen dyes, such as lacmus, were known in Germany in the Middle Ages, they were bought in Norway by the Hanse merchants, and exported to Germany and England. The first record of this practice dates from 1316.

Saffron was perhaps more popular as a spice than as a dye. It was one of the chief trade commodities, and the beauty of its yellow blossoms invariably excited admiration. The most important of the Merchants' Companies of Basle was known as "the Saffron". The saffron lily was its coat of arms, and also that of Florence, and of the Town of Saffron Walden in Essex. In Semifonte, a town destroyed in 1202 by the Florentines, it was considered easier to raise money on a couple of pounds of saffron than by mortgaging real estate. In 1224 a pound was valued at 24 solidi in San Gimignano, as compared with 19-20 solidi six years earlier. Its value was evidently increasing.

Saffron was perhaps more popular as a spice than as a dye. It was one of the chief trade commodities, and the beauty of its yellow blossoms invariably excited admiration. The most important of the Merchants' Companies of Basle was known as "the Saffron". The saffron lily was its coat of arms, and also that of Florence, and of the Town of Saffron Walden in Essex. In Semifonte, a town destroyed in 1202 by the Florentines, it was considered easier to raise money on a couple of pounds of saffron than by mortgaging real estate. In 1224 a pound was valued at 24 solidi in San Gimignano, as compared with 19-20 solidi six years earlier. Its value was evidently increasing.

Indigo became the most popular of all dyes. It was without doubt known to the Middle Ages. Marco Polo, that daring adventurer who travelled through Asia at the end of the 13th century, and whose vivid account of his travels is one of the most important sources of our knowledge for that period, refers to indigo and brazil-wood, which he calls sappan, as to something familiar. He describes in detail "the manufacture of indigo in the kingdom of Kulam on the west coast of India, where it is produced in great quantities and in excellent quality. It is won from a species of herb, which is plucked out by the roots, and put into tubs of water, where it is left to rot. Then the sap is pressed out, which, when exposed to the sun, evaporates, leaving a kind of paste behind it, which is cut up into small pieces of the shape also familiar to us". In Gujerat and Cambai in North West India he also found indigo production.

The great advantage of indigo over the native woad consists in a concentration of pigment equal to ten times that of its rival, and which is extracted in the manner described above.

It is an interesting detail in the development of civilization to trace how the native dyes were superseded by gall, logwood, and brazilwood, and how indigo assumed the position formerly held by woad. Today it, too, has been driven from the market, together with all the other natural dyes, by the aniline dyes. Even in the bazaars of India only European dyes are to be found today and in the workshops of the Indian dyers we should seek in vain for even a scrap of indigo.

Tags:

Replies to This Discussion

Events

-

2014 is the Chinese Year of the Horse

February 17, 2026 at 12am to February 5, 2027 at 12am – where & how you choose

Birthdays

Birthdays Tomorrow

Important (read & understand)

Skype: Travelingraggyman

Email and Instant Messenger:

TravelerinBDFSM @ aol/aim; hotmail; identi.ca; live & yahoo

OR

Travelingraggyman @ gmail and icq ***

1AWARD UPDATES & INFORMATION

10,000 votes - Platinum Award

5,000 votes - Gold Award

2,500 votes - Silver Award

1,000 votes - Bronze Award

300 votes - Pewter Award

100 votes - Copper Award

Member of the Associated Posting System {APS}

This allows members on various sites to share information between sites and by providing a by line with the original source it credits the author with the creation.

Legal Disclaimer

***************We here at Traveling within the World are not responsible for anything posted by individual members. While the actions of one member do not reflect the intentions of the entire social network or the Network Creator, we do ask that you use good judgment when posting. If something is considered to be inappropriate it will be removed

Site Meter

This site is strictly an artist operational fan publication, no copyright infringement intended

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries had its humble beginnings as an idea of a few artisans and craftsmen who enjoy performing with live steel fighting. As well as a patchwork quilt tent canvas. Most had prior military experience hence the name.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries.

Vendertainers that brought many things to a show and are know for helping out where ever they can.

As well as being a place where the older hand made items could be found made by them and enjoyed by all.

We expanded over the years to become well known at what we do. Now we represent over 100 artisans and craftsman that are well known in their venues and some just starting out. Some of their works have been premiered in TV, stage and movies on a regular basis.

Specializing in Medieval, Goth , Stage Film, BDFSM and Practitioner.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries a Dept of, Ask For IT was started by artists and former military veterans, and sword fighters, representing over 100 artisans, one who made his living traveling from fair to festival vending medieval wares. The majority of his customers are re-enactors, SCAdians and the like, looking to build their kit with period clothing, feast gear, adornments, etc.

Likewise, it is typical for these history-lovers to peruse the tent (aka mobile store front) and, upon finding something that pleases the eye, ask "Is this period?"

A deceitful query!! This is not a yes or no question. One must have a damn good understanding of European history (at least) from the fall of Rome to the mid-1600's to properly answer. Taking into account, also, the culture in which the querent is dressed is vitally important. You see, though it may be well within medieval period, it would be strange to see a Viking wearing a Caftan...or is it?

After a festival's time of answering weighty questions such as these, I'd sleep like a log! Only a mad man could possibly remember the place and time for each piece of kitchen ware, weaponry, cloth, and chain within a span of 1,000 years!! Surely there must be an easier way, a place where he could post all this knowledge...

Traveling Within The World is meant to be such a place. A place for all of these artists to keep in touch and directly interact with their fellow geeks and re-enactment hobbyists, their clientele.

© 2024 Created by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler.

Powered by

![]()