Traveling within the World

Linking your favorite traveling artists across the globe

Iron Production in the Viking Age

Iron Production in the Viking Age

|

Although Norse people knew of mining and mined some iron ore in a variety of locations throughout Scandinavia, most Viking era iron was smelted from bog iron. The photo to the left shows the bog at Rauðanes in Iceland, where Skallagrímur Kveldúlfsson, one of the early settlers in Iceland, had his smithy. Chapter 30 of Egils saga describes him as a "great smith" who "smelted a lot of bog iron in winter". |

|

The saga says that Skallagrímur couldn't find an anvil stone to suit him, so he rowed out into Borgarfjörður one evening in his boat. He dove to the bottom and brought up a suitable boulder for his anvil stone. The anvil stone, with its hammer marks, still stands at Rauðanes (left), but it has been moved away from the shore. Ruins (right), which are the probable site of Skallagrím's smithy, are located closer to the shore. |

|

At the Norse settlement in L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada, there is clear evidence that Norsemen harvested and smelted bog iron to use as the raw material for the iron rivets they fabricated to repair their ships there 1000 years ago. Where streams run from nearby mountains through a peat bog, bog iron can almost always be found. That combination was probably visible to Norse explorers even from on board their ships in the cove at L'Anse aux Meadows. It occurs in glaciated regions throughout the world, and so would have been very familiar to the Norse explorers at Vínland. |

|

|

Streams carry dissolved iron from nearby mountains. In the bog, the iron is concentrated by two processes. The bog environment is acidic, with a low concentration of dissolved oxygen. In the acidic environment of the bog, a chemical reaction forms insoluble iron compounds which precipitate out. But more importantly, anaerobic bacteria (Gallionella and Leptothrix) growing under the surface of the bog concentrate the iron as part of their life processes. Their presence can be detected on the surface by the iridescent oily film they leave on the water (left), another sure sign of bog iron. In Iceland (right), the film is called jarnbrák (iron slick). |

|

When a layer of peat in the bog is cut and pulled back using turf knives (right), pea sized nodules of bog iron can be found and harvested. Although the iron nodules are reasonably pure, there aren't many of them. They are, however, a renewable resource. About once each generation, the same bog can be re-harvested. |

|

|

In some regions (particularly Sweden), iron ore, rather than bog iron, was the raw material for smelting. The ore was in the form of "red earth" (rauði), a powdery ocher. Regardless of the source, the raw materials were usually roasted to drive off moisture before being smelted. The roasting also served to "crack" the surface of the iron ore, making it more porous so that the gases in the smelting furnace could enter and react with the iron more easily. Once the dry nodules or ore was in hand, the lengthy process of smelting the iron began. |

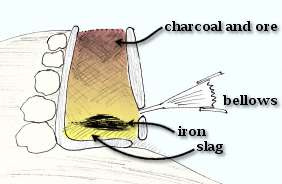

Smelting furnaces were small, clay-lined shafts made of stone. They were roughly circular, about 80cm (32 in) tall and 30cm (12in) in diameter. Charcoal was the usual fuel, which was mixed with the ore and added to the top of the furnace as the smelting progressed. An air blast was supplied through the side of the furnace with a bellows which raised the temperature to 1100-1300ºC (2000-2400ºF) at the bottom of the furnace near the iron. Slag (consisting of oxides of iron, silicon, and other elements) was the waste product of the smelting process and was drained through a port at the bottom of the furnace. |

|

Inside the furnace, a reducing atmosphere was created, rich in carbon monoxide. The gas scavenged the oxygen from the iron compounds in the ore, converting them to elemental iron:

Not surprisingly, the reactions are considerably more complex than this simple equation would indicate. The temperature in the furnace ranged from 300ºC near the top to as high as 1300ºC near the bottom. Different chemical reactions occurred in the different temperature zones of the furnace. Throughout the smelting process, additional fuel and ore was added at the top of the furnace. The process was tended constantly, adjusting the fuel, ore, and air to optimize the results. The smelting operation lasted for many hours. (The photo to the right shows flames leaping from the furnace as the bellows were worked during a night-time smelting operation.) |

|

|

When the fire finally died, amongst the ash, slag, and charcoal in the bottom of the pit was a frothy iron sponge (left), called a bloom. By repeatedly heating and working this iron, more impurities were mechanically removed. The desired end result was a malleable low-carbon iron, ready to be forged to fabricate the required articles. Because the smelting process is difficult to control, the quality of the iron obtained was highly variable. In addition, the process was very inefficient; a lot of iron was left in the slag. |

At L'Anse aux Meadows, the iron was probably used to make rivets and washers for ship repair. The wrought iron was rich in silicate impurities, which formed a glassy surface on the iron. This is visible on the parts even today (right). The surface helped protect the iron from rust, even when immersed in sea water. |

|

|

Most domestically produced iron in the Norse era was tediously produced from bog iron. Because of the time consuming processes used to create it, smelted iron was valuable. Roughly worked iron bars were used as trade goods (left). These bars are from Norway and are about 30cm (12 inches) long. |

The axe head blanks shown to the right were also trade goods. They were probably exported from Norway and were on their way to a trading center in Denmark when they were lost. They are about 20cm (8inches) long and were found threaded on a wooden stave for convenient handling during shipping. |

|

|

Because of their expense, iron tools and weapons were highly valued. The loss of an iron tool from a Norse farmstead was a disaster, especially if it were a major tool like an axe or scythe. A typical farm in the Viking age probably owned no more than 40-50kg (100lbs) of iron, in the form of tools, weapons, and cooking equipment. The Mästermyr chest (a reproduction is shown to the left) is an oak tool chest filled with tools that belonged to a master smith in the 11th century. The chest and its contents were found in Mästermyr, Sweden in 1936. The chest contained an assortment of tools for working wood and metals (including hammers, axes, adzes, saws, spoon-borers, tongs, shears, files, and others), along with raw materials and finished products. It's been suggested that its owner lost the chest while crossing the mýrr (bog) that gives Mästermyr its name. The loss must have been a devastating blow to its owner. |

The remains of the smithy at Stöng in Iceland are shown to the right. The foundation stones are visible around the periphery, and the dished stone in the center held water to cool the workpiece. However, the interpretation of Viking age smithies remains troublesome. |

|

|

Surviving anvil stones are quite low to the ground, too low for comfortably working on a piece. The anvil stone at Aðalból in East Iceland is shown to the left. At Reykholt, a depression was found next to the location of the anvil stone. It has been suggested that the smith sat on the ground next to the anvil with his legs in the hole on the ground as he hammered at the anvil. Modern smiths I've talked to don't find this interpretation convincing. On the other hand. the wood carving from a 12th century church in Norway (shown to the right) illustrates a scene from a Norse heroic myth in which Reginn reforges a sword for his foster brother Sigurðr. As depicted in this carving, the anvil seems uncomfortably low to the ground. Perhaps smiths in the Viking age routinely worked at heights that modern smiths find awkward. |

|

It seems likely that iron arms and armor were treasured and passed from generation to generation. Lifetimes of hundreds of years seem possible for some iron articles such as helmets. When one compares the probable date of manufacture with the probable date of burial of some archaeological finds, one is forced to conclude that some iron items were used for a century or more before being buried with their final owner. |

http://www.hurstwic.org/history/articles/manufacturing/text/bog_iro... |

Tags:

Replies to This Discussion

Events

-

2014 is the Chinese Year of the Horse

February 17, 2026 at 12am to February 5, 2027 at 12am – where & how you choose

Birthdays

Important (read & understand)

Skype: Travelingraggyman

Email and Instant Messenger:

TravelerinBDFSM @ aol/aim; hotmail; identi.ca; live & yahoo

OR

Travelingraggyman @ gmail and icq ***

1AWARD UPDATES & INFORMATION

10,000 votes - Platinum Award

5,000 votes - Gold Award

2,500 votes - Silver Award

1,000 votes - Bronze Award

300 votes - Pewter Award

100 votes - Copper Award

Member of the Associated Posting System {APS}

This allows members on various sites to share information between sites and by providing a by line with the original source it credits the author with the creation.

Legal Disclaimer

***************We here at Traveling within the World are not responsible for anything posted by individual members. While the actions of one member do not reflect the intentions of the entire social network or the Network Creator, we do ask that you use good judgment when posting. If something is considered to be inappropriate it will be removed

Site Meter

This site is strictly an artist operational fan publication, no copyright infringement intended

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries had its humble beginnings as an idea of a few artisans and craftsmen who enjoy performing with live steel fighting. As well as a patchwork quilt tent canvas. Most had prior military experience hence the name.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries.

Vendertainers that brought many things to a show and are know for helping out where ever they can.

As well as being a place where the older hand made items could be found made by them and enjoyed by all.

We expanded over the years to become well known at what we do. Now we represent over 100 artisans and craftsman that are well known in their venues and some just starting out. Some of their works have been premiered in TV, stage and movies on a regular basis.

Specializing in Medieval, Goth , Stage Film, BDFSM and Practitioner.

Patchwork Merchant Mercenaries a Dept of, Ask For IT was started by artists and former military veterans, and sword fighters, representing over 100 artisans, one who made his living traveling from fair to festival vending medieval wares. The majority of his customers are re-enactors, SCAdians and the like, looking to build their kit with period clothing, feast gear, adornments, etc.

Likewise, it is typical for these history-lovers to peruse the tent (aka mobile store front) and, upon finding something that pleases the eye, ask "Is this period?"

A deceitful query!! This is not a yes or no question. One must have a damn good understanding of European history (at least) from the fall of Rome to the mid-1600's to properly answer. Taking into account, also, the culture in which the querent is dressed is vitally important. You see, though it may be well within medieval period, it would be strange to see a Viking wearing a Caftan...or is it?

After a festival's time of answering weighty questions such as these, I'd sleep like a log! Only a mad man could possibly remember the place and time for each piece of kitchen ware, weaponry, cloth, and chain within a span of 1,000 years!! Surely there must be an easier way, a place where he could post all this knowledge...

Traveling Within The World is meant to be such a place. A place for all of these artists to keep in touch and directly interact with their fellow geeks and re-enactment hobbyists, their clientele.

© 2025 Created by Rev. Allen M. Drago ~ Traveler.

Powered by

![]()